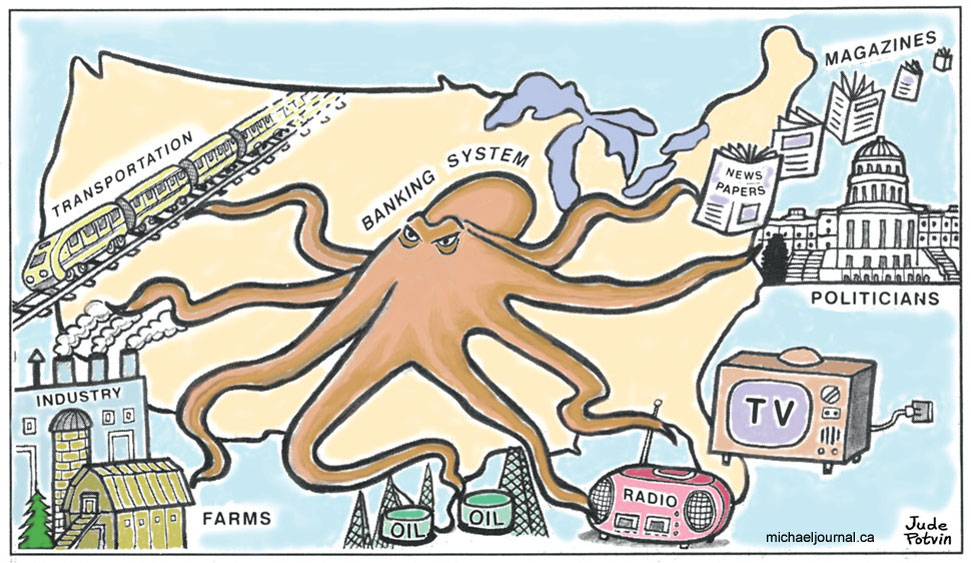

International Finance has no country. It covers all, is from everywhere, stretches out its tentacles all over where there is plunder to take, scatters innumerable ruins, and does not hold itself responsible for anything. "Where a man’s fortune is, there is his country," Pope Pius XI rightly wrote in his encyclical letter Quadragesimo Anno.

Naturally, you find neither bankers nor financiers in forests that are being cleared. Their time will come later. We draw the following information from the book of Gertrude Coogan, Money Creators, published in Chicago in 1935.

When America was in its infancy, fighting against the wild animals or the hostile Indians, the Colonists remained free enough to choose their medium of exchange, their money, and to issue it in the measure of their needs. The first charter of Virginia, in 1606, that of Massachusetts, in 1628, and the customs of New England in the eighteenth century, are there to prove it.

But when the American Colonies emerged from their years of tribulation, and became fertile sources of production, the lusts of the motherland (England) searched the means to usurp a good part of it.

The Bank of England, founded in 1694, was already inspiring the laws of the London Government. In 1767, the British Chancellor of the Exchequer, having proposed various duties on glass, chinaware, paper, pasteboard, colors, tea, etc., in order to grow rich at the expense of the American Colonists who were obliged to buy these things in England, a Member of Parliament, Grenville, stood up and, calling all these things as trifles, said:

"I will tell the members of this House the simplest and the most efficacious means to assure us of something in America: make paper money here for the Colonies, declare it the only legal money, and lend it to the Colonists with interest. With the interest, you will obtain what you wish to have."

The advice appeared to be good. On this, a certain Mr. Townsend stood up and introduced before the House a bill all prepared for that purpose. Of course, it would be the Bank of England that would issue the paper money for the Colonies and, by the interest, would hold them under its thumb.

It was because of this rapacity of the London Financiers that the American Colonies rebelled against England. They wanted to keep the right to make their money according to their needs, and they refused to pay tribute on their medium of exchange.

So, the Americans did take good care to expressly declare in their Constitution (Article 1, Section 8, Paragraph 5): "Congress shall have the power to coin money and to regulate the value thereof."

The Americans won the war. Their Constitution remains. But it is not the Congress that issues money, not the Congress that regulates the volume of it, therefore, it is not the Congress that determines the value of it. The Congress remains powerless in front of the lack of money that reduces millions of Americans to misery in a plentifully rich country.

How did this happen? It is that, if the English Government lost the war, the International Financiers won theirs, and they continue to speculate upon America as a colony of International Finance. Besides, it was not a prey to be released. Everything was to be done so as to keep in leash a continent that was already giving signs of a prodigious future.

In all of the large-scale operations to take a country in their meshes, the Masters of Finance operate through generally unsuspected middlemen. One is very careful not to compromise them by never letting the objectives known. Finance even sees to it that the press of the concerned countries exalts these men as eminent citizens or skillful businessmen. It makes use of its influences to have them publicly honored.

The man of the hour at the cradle of the American Republic was Alexander Hamilton. He was born in the West Indies. His father, one Levine, was a wealthy planter. His mother, Rachel, was unfaithful, and the two spouses divorced about two years after Alexander’s birth. The wife took a second husband, by the name of James Hamilton, and it is this name which later Alexander adopted.

Alexander had a precocious mind, and was conspicuous in everything that concerned figures, finance, money... As young as the age of thirteen, he was at the service of the richest merchant in the Caribbean. At seventeen years of age, he came to New York. It is there that he was to die in 1804, in a duel with a business and political rival, Aaron Burr.

Alexander Hamilton Alexander Hamilton |

Hamilton took part in the war for the American independence and was, for a while, secretary to General George Washington. He took advantage of his leisure time to avidly study all that concerns money, coin, gold, silver, and foreign exchange. His mind was particularly admiring the system of a central bank owned by private individuals, and provided with sovereign privileges, like the Bank of England. He found ideal this submission of the great human mass to a group of a privileged few.

During the War for Independence, the rebel Colonies issued a national currency. The European Financiers, the creators and lenders of the debt-money, who were already governing the world, were not able to tolerate such boldness. They made use of their powers and of their relations to have the value of this American money drop.

Such power into the hands of private individuals, operating without the hindrance from the frontiers, struck Hamilton, and stimulated him in his researches. He wanted to know how some individuals were able to exercise such a power, not to fight them, but to imitate them.

He stuck more and more to the idea of the control of a nation’s money by a private bank cooperating with the International Money Powers. He especially encouraged himself to the idea that it was relatively easy to impose such a system to an ignorant and unsuspecting public.

During the war period, Hamilton was already nurturing plans to make a success of the same iniquity in his country. On April 30, 1781, the 24-year-old Hamilton, who had succeeded to gain a hold on Robert Morris, administrator of the Public Revenue Department for Washington, did dare write to him:

"A national debt, if it is not excessive, will be a national blessing, a powerful cement of union, a spur to industry." Do our present governors of central banks think differently?

We are in 1789. The American Constitution having just been adopted, George Washington, appointed president, proceeds to the formation of his first cabinet. He wants to entrust the Treasury to Morris. To his great surprise, Morris refuses and recommends Hamilton. And Washington makes the great error of his Administration, which will compromise all his work. Hamilton becomes the first U.S. Secretary of the Treasury. (The equivalent of the Minister of Finance in Canada, or the Chancellor of the Exchequer in England.)

Benjamin Franklin, who had enjoyed a strong influence on the public opinion, died in 1790. From now on, Hamilton feels more free to execute his plans, to realize the desired work. But he must maneuver. The U.S. Constitution is clear, and reserves to the Congress the coining and the issuance of money. If Franklin is dead, the patriot Thomas Jefferson is always there and watches over a work to which he took so great a part. Jefferson is then, in Congress, the leader of an honest debt-free money system; here is one of his quotes:

Thomas Jefferson Thomas Jefferson |

"I believe that banking institutions are more dangerous to our liberties than standing armies. Already they have raised up a money aristocracy that has set the Government at defiance. The issuing power should be taken from the banks, and restored to the people."

The debt of the States, contracted especially for the conduct of the war, rises to 75 million dollars, a part due to foreign private capitalists, a part to some private individuals in the country who had received this money from the Rothschilds of Frankfurt to make it bear interest in a country at war, a part to some investors.

The new nation needs a medium of exchange, money, to allow the running of business. The nation being sovereign, a wise means would be to coin or to print the needed money, in silver or paper, and to put this money into circulation by repurchasing its debt.

Hamilton has another philosophy. He proposes that the debt be converted into interest-bearing bonds. Instead of creating free money for circulation, which would repurchase the debt in paying an average of $19 per capita, he prefers to fund a core of national debt of $19 per capita. And Hamilton studies the means to have a thing so opposed to the ideals of the Republic, accepted.

By his functions, Hamilton is held to keep secret his report and his projects until he introduces them for discussion to the Congressmen. But he makes a point of approaching, one by one, the more influential Congressmen, except, however, the known incorruptible ones. He makes each one think that he is the only one let into the secret, and suggests that he draw profit from the transaction.

The international speculators had had the war-debt certificates beaten down to 15% of their face value. In view of the fact that the Government will repurchase them by an issuance of bonds, and will be held responsible for the payment of the interests, the securities will obviously rise. Also, every Congressman possessing the "official secret" hastens to go as far as in the most remote places to buy the dropping certificates which were driving their holders to despair.

Corruption produces its fruits. When Hamilton introduces his project, the most influential Congressmen have in their wallet the papers likely to at least quintuple or sextuple in value as soon as the carrying of the proposition. They hasten therefore to approve the funding of the public debt by State bonds on which the laborious but ignorant public will pay interest. The most democratic among the democracies thus defiles its virginity; politicians already grow fat in sacrificing their electors.

It was no use for Jefferson to protest against "a prostitution of laws which constitute the pillars of our whole system of jurisprudence." It was no use for the agricultural class to conform to the line of Jefferson. Communications are slow at this time; Alexander Hamilton’s debt-philosophy, supported by compromised representatives, is imposed to the young nation.

It remains to seal the work by the establishment of a private bank, to create and issue money according to the principles of the Bank of England. The Secretary of the Treasury tackles it in 1791. Obviously, he has to face up to Jefferson, Madison, Adams, and a few others. Thomas Jefferson, the first Secretary of State, urged President Washington to veto the new bank, in these words:

"If the American people ever allow the private banks to control the issue of currency, first by inflation and then by deflation, the banks and corporations that will grow up around them will deprive the people of all property until their children will wake up homeless in the continent their fathers conquered."

But Hamilton can rely on the assistance of compromised Congressmen, and he now excels in the art of deceiving and of smearing. Let us listen to his virtuous argumentation:

"The emitting of paper money by the authority of Government is wisely prohibited to the individual states by the national Constitution; and the spirit of that prohibition ought not to be disregarded by the Government of the United States. The wisdom of the Government will be shown by never trusting itself with the use of so-dangerous and seductive an expedient."

After having removed the credit from the control of the inferior states, this control will be passed on from the control of the Central State to that of the private financiers. Don’t our centralizers tend to do that nowadays?

And the House of Representatives votes for the private bank. George Washington, fearing of this sabotage, asks Madison to prepare a veto. But he finally wavers before the persuasive eloquence of the witty Hamilton. The "financial expert" is the vanquisher of the great general and statesman.

As a crowning, Hamilton is the honor guest at a special reception given by the Chamber of Commerce of New York City, to celebrate the triumph of finance over the nation.