u

Blessed Hildegard Burjan

Foundress of the Sisters of Social Charity

by

Dom Antoine Marie osb

One evening, a little girl saw, from her bedroom

window, some women dressed in white, walking

back and forth in a garden while chanting psalms.

She asked her mother what they were doing. “They’re

nuns. They’re praying.” The little girl went on, “What

is a nun? And who are they praying to?” — “They’re

praying to their God.” — “Where is God? Why are

they praying instead of going to bed? ” The mother,

agnostic, did not know how to answer. “How good it

must be to be able to pray to God...” sighed the little

girl, who added, under her breath, “My God, I also

want to pray ! ” Hildegard had just taken her first step

on a long path in search of Truth.

Hildegard Lea Freund was born

on January 30, 1883 in Goerlitz, Sax-

ony (on the present-day German-

Polish border), into a family of non-

practicing Jews. In 1895, the Freund

family moved to Berlin, where Hilde-

gard went to high school. She dis-

played great intellectual gifts and a

deep desire for moral integrity; she

wanted to become an “ethical per-

son,” which for her meant a woman

of conviction and principles. She

was not concerned about those

things that typically excite teenagers

— clothes, pastimes, being in the

popular group... Rather, she was in-

terested in philosophy, art, and cul-

ture. Nevertheless, her gaze did not

extend beyond the present life. After

reading Schopenhauer, for whom

belief in a transcendent absolute

and seeking eternal happiness were

nothing but a vain illusion, she would write a poem

with the disillusioned refrain, “Joys and sorrows pass.

The world passes — there is nothing! ”

Already before the birth of Jesus Christ, the Book

of Wisdom put on the lips of unbelievers these words:

We were born by mere chance, and hereafter we shall

be as though we had never been (Wis. 2:2). After her

conversion, Hildegard confided, about someone who

had committed suicide: “So why should one struggle

with this world, if one does not believe in the here-

after ? I am sure that I too would kill myself if I did

not believe. I do not understand how people can live

without believing in God.” Pope Benedict XVI likewise

observed, in the encyclical

Caritas in Veritate

, “With-

out God man neither knows which way to go, nor even

understands who he is” (no. 78).

In 1899, the Freund family moved to Zurich, Switz-

erland. After graduating high school in 1903, Hilde-

gard entered the university, a rare privilege for young

women in her day. She studied German literature and

philosophy, under two Protestant professors, Saits-

chik and Foerster, who taught a system called the

“philosophy of life,” which, counter to the prevailing

rationalism, affirmed that man was capable of know-

ing God. Saitschik insisted that purity of heart and up-

rightness of soul were necessary for such knowledge.

Hildegard, moved but not convinced, repeated over

and over, in tears and supplication, the “prayer of the

unbeliever”: “My God, if You exist, let me find You ! ”

But for the moment she received no response.

The deep meaning of life

In 1907, Hildegard returned to

Berlin to study economics and so-

cial policy. There, she met Alexan-

der Burjan, a Jewish Hungarian en-

gineer who was agnostic and, like

her, was seeking the deep mean-

ing of life. They married within the

year. In October 1908, an attack of

renal colic forced the young woman

to be hospitalized in the Saint Hed-

wig Catholic hospital in Berlin. Her

health deteriorated to the point that

she had to undergo several oper-

ations. During Holy Week of 1909,

she was at the point of death, and

the doctors had lost all hope of sav-

ing her. Against all expectations, on

Easter Monday, her health markedly

improved. After seven months of

hospitalization, she was able to re-

turn home. However, she would suf-

fer from the aftereffects of this kidney condition for the

rest of her life.

During her long stay in the hospital, Hildegard

had admired the devotion and charity of the Sisters

of Mercy of Saint Borromeo (members of an Order

founded by Saint Charles Borromeo, the archbishop

of Milan, who died in 1584). She observed, “Only the

Catholic Church can achieve this miracle of filling an

entire community with such a spirit... Man, left to only

his natural faculties, cannot do what these Sisters do.

In seeing them, I experienced the power of grace.” It

was after this revelation of the “unshakable truth” of

the Church through the holiness of her members that

Hildegard converted. After a period of catechumen-

ate, she received Baptism on August 11, 1909. This

decisive act was the culmination of a long spiritual

journey. After having long thought that man could, by

dint of intelligence and will, achieve moral progress

on his own, she now wrote, “It is not by human wis-

dom alone that we can do good, but only in union with

Christ. In Him we can do all things; without Him, we

are completely helpless.”

“Man does not develop through his own powers,”

wrote Pope Benedict XVI in Caritas in Veritate...

“In the

course of history, it was often maintained that the

creation of institutions was sufficient to guarantee

the fulfillment of humanity’s right to development.

Unfortunately, too much confidence was placed in

those institutions, as if they were able to deliver the

desired objective automatically. In reality, institutions

by themselves are not enough, because integral hu-

man development is primarily a vocation ... Moreover,

such development requires a transcendent vision of

the person, it needs God: without Him, development

is either denied, or entrusted exclusively to man, who

falls into the trap of thinking he can bring about his

own salvation, and ends up promoting a dehuman-

ized form of development. Only through an encounter

with God are we able to see in the other something

more than just another creature, to recognize the div-

ine image in the other, thus truly coming to discover

him or her and to mature in a love that becomes con-

cern and care for the other”

(no. 11).

The child must live !

Baptism was for Hildegard the beginning of a new

life. Radiant, she confided her happiness to her clos-

est family and friends. In August 1910, she had the joy

of seeing her husband Alexander baptized. Shortly

thereafter, Hildegard was pregnant and preparing for a

difficult delivery. The doctors advised her to abort her

child because of the grave risk she was running. But

she vigorously refused: “That would be murder ! If I

die, I will then be a victim of my ‘profession’ of mother,

but the child must live ! ” The delivery went well, and

little Lisa was born. She would be the only child in the

Burjan family, whose life would from that point on un-

fold in Vienna, where Alexander became the head of a

telephone equipment company.

Hildegard was certain that her life, saved by provi-

dence, must be entirely consecrated to God and man-

kind. Her vocation would be to proclaim to the poor

God’s love for them through social action. Before long,

she discovered the terrible reality of workers’ condi-

tions. The poor, newly arrived in Austria’s capital, lived

crammed into unsanitary tenements. Men, women,

and children worked in factories twelve to fifteen

hours a day for starvation wages. In this environment,

women were often tempted to prostitute themselves

and abandon their children. To remedy the situa-

tion, the Church would create associations of Cath-

olic women to fight not only to protect the morals of

women factory workers, but also to defend their rights

in the face of unscrupulous employers. Hildegard com-

mitted herself wholeheartedly to these efforts, armed

with the deep understanding of social issues she had

acquired at the university. In particular, she came to

the defense of workers who worked at home and were

paid at the employer’s discretion, without any social

security whatsoever.

In September 1912, Hildegard spoke at the annual

gathering of Catholic women’s leagues in Vienna: “Let

us examine if we are not complicit in the misery of the

people. We should buy only from conscientious shop-

keepers, not pushing them to lower their prices, but

demanding from time to time that the manufacturers

account for the origin of their products. Too often, the

well-off woman pressures storekeepers to sell at un-

realistic prices, which is always at the expense of im-

poverished home workers.” Almost alone at the out-

set in defending these workers “without a voice”, she

soon recruited volunteer collaborators from among

the well-to-do.

Little slaves

That same year, Hildegard founded the “Associa-

tion of Christian Women Home Workers,” which of-

fered its members better wages, social protection,

legal assistance, and the possibility of an education. At

the cost of great effort and frequent humiliations, she

tried to win the support of those who were reluctant,

even hostile. She thought that women had the right to

a profession, including an intellectual one, to the ex-

tent that the work would not infringe upon their natural

roles as wives and mothers. But this right must not

be a pretext for exploiting their weakness. She also

attended to the needs of children who were forced to

earn a living — one-third of children in Vienna were in

this situation. In violation of the law, children as young

as six were working 14 hours a day, in factories or at

home. These little slaves suffered an appalling mortal-

ity rate. Even those who survived into adulthood re-

mained mentally impacted.

Hildegard in 1905: “My God, if

You exist, let me find You! ”

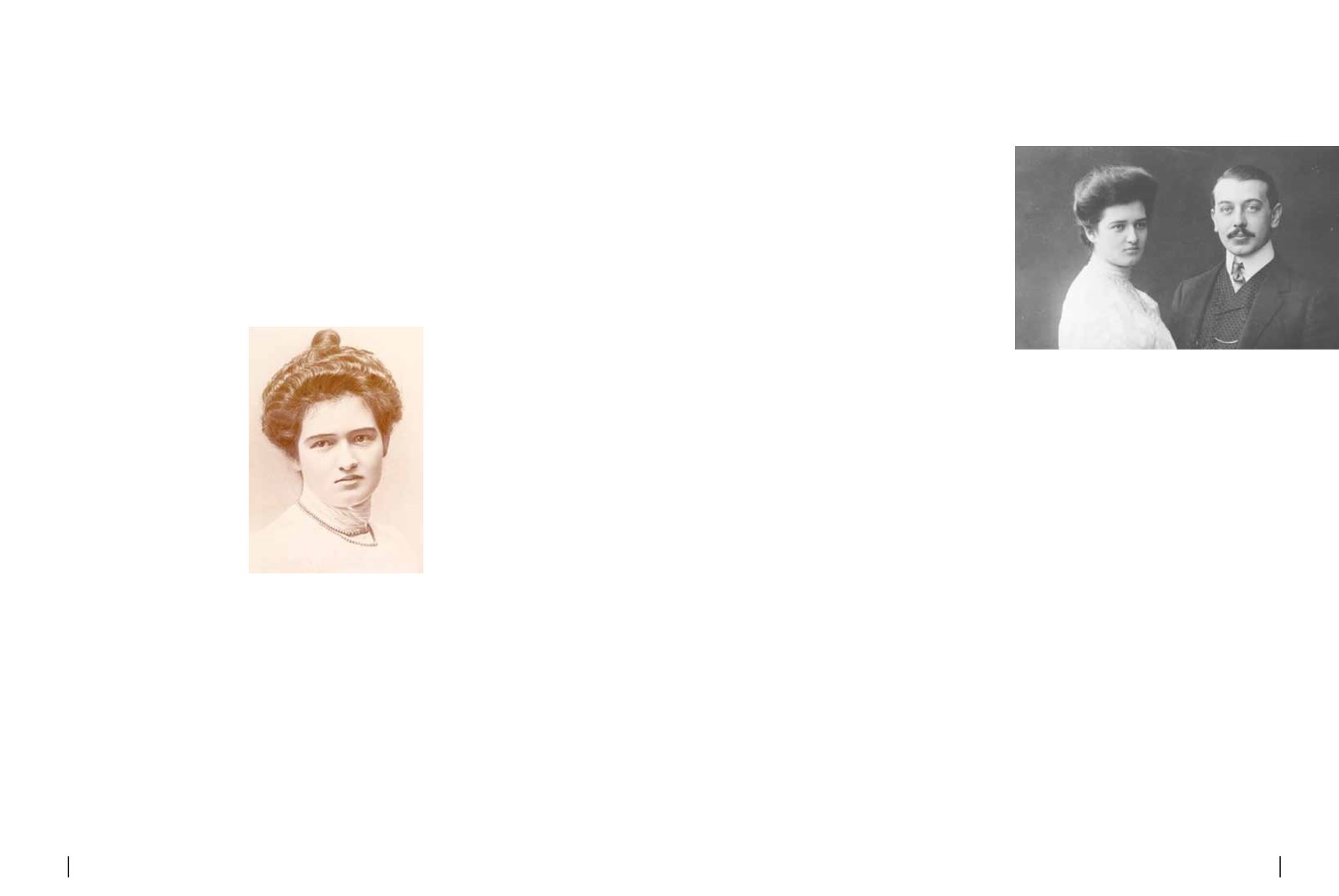

Hildegard and her husband Alexander Burjan

40

MICHAEL October/November/December 2013

MICHAEL October/November/December 2013

www.michaeljournal.org www.michaeljournal.org41