The Social Credit proposals

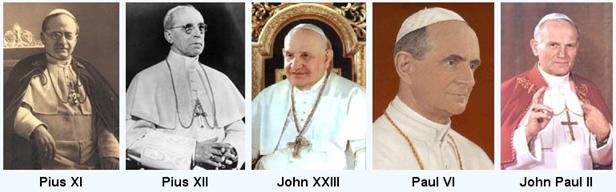

explained in 10 lessons

Louis Even

and C. H. Douglas

and

viewed in the light of

the social doctrine of the Church

A study prepared by Alain Pilote

on the occasion of the week of study

that followed the Congress of the Pilgrims of Saint Michael

in Rougemont, September 5-11, 2006

Published by the Louis Even Institute for Social Justice

1101 Principale St., Rougemont,

QC, Canada J0L 1M0 — www.michaeljournal.org

The Social Credit proposals

explained in 10 lessons

Lesson

1 : Le goal of economics: to bring goods to those who need them

Lesson 2 : Poverty amidst plenty, the birth of money

Lesson 3 :

Banks create money as a debt

Lesson 4 :

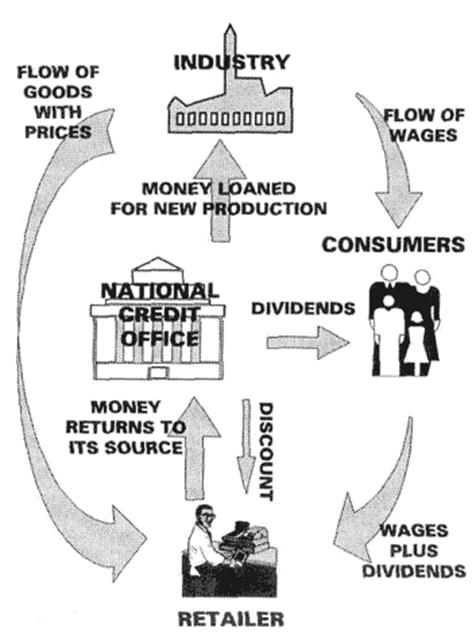

The solution: debt-free money created by society

Lesson 5 : The chronic shortage of purchasing power

— The dividend

Lesson 6 : Money and prices — The compensated

discount

Lesson 7 :

The history of the banking control in the United States

Lesson 8 : Social Credit is not a political party

Lesson 9 : Social Credit and the social doctrine of

the Church (Part I)

Lesson 10 : Social Credit and the social doctrine

of the Church (Part II)

Introduction

Social Credit is a doctrine, a series of principles

set down for the first time by Major and engineer C. H. Douglas in 1918. The

implementation of these principles would make the social and economic organism

effectively serve its proper purpose or end, that is, to meet human needs.

Social Credit would create neither the goods nor the needs; what it would do is

to eliminate the present artificial obstacle between goods and needs, between

production and consumption, between the wheat in elevators and the bread on the

table. The obstacle today — at least in the developed countries — is purely of

financial order, a money obstacle. The financial system does not proceed from

God, and nor does it come from nature. Established by man, it can be adjusted

to serve man and cease to enslave him.

Social Credit presents concrete propositions for

exactly this purpose. Though very simple, these propositions embody a real

revolution. Within it, Social Credit holds the vision of a new civilization, if

civilization means man's relationship with his fellow man and the conditions of

life that foster for each one the blossoming of his personality.

Under a Social Credit system, we would no longer

struggle with problems that are strictly financial, problems that constantly

plague public administrations, institutions and families, problems which poison

relationships between individuals. Finance would be nothing more than an

accounting system which expresses in figures the relative values of goods and

services. This system would serve to mobilize and coordinate the energies and

effort involved in the different levels and stages of production that lead to the

finished goods. It would distribute to ALL consumers the means to choose freely

and individually, what is suitable to them from among the goods offered or

immediately realizable.

For the first time in history, absolute economic

security, without restrictive conditions, would be guaranteed to each and every

one. Material poverty would be a thing of the past. Material anxiety about

tomorrow would disappear. Bread would be ensured to all, while there is enough

wheat to make enough bread for all. Similarly for the other goods that are

necessary for life.

Each citizen would be presented with this economic

security as a birthright, as a member of the community, enjoying throughout

one’s life an immense community capital, that has become a dominant factor of

modern production. This capital is made up of, among other things, natural

resources, which are a collective good; life in society, with the benefit that

ensues from it; the sum of the discoveries, inventions, technological progress,

which are an ever-growing heritage from previous generations.

This

community capital, which is so productive, would bring to its co-owners, each

citizen, a periodical dividend, from the cradle to the grave. With the volume

of production coming from the common capital, the dividend to each ought to be

at least sufficient to cover the basic necessities of life. This dividend would

be distributed equally, in equal amount, to all. It would also be given to

those who personally take part in production, independently of wages, salaries,

or other forms of reward received.

An income like this attached to the individual, and no

longer only attached to his status of employee, would protect him from

exploitation by other human beings. With the basic necessities of life guaranteed,

a man can better resist being pushed about and can better take up the career of

his own choosing. Freed from urgent material worries, people could apply

themselves to activities which are more creative than compulsory and routine

work, and strive towards their own development by the exercise of human

capabilities superior to the purely economic function. Getting the daily bread

would no more be the all-absorbing occupation of their lives.

Note: The text of the following 10 lessons is

Note: The text of the following 10 lessons is

essentially taken from Louis Even’s

writings :

essentially taken from Louis Even’s

writings :

In This Age of Plenty,

What Do We Mean by Real Social Credit?

A Sound and Efficient Financial System

LESSON 1 — THE GOAL OF ECONOMICS:

TO BRING GOODS

TO THOSE WHO NEED THEM

Ends and means

In talking of economics, it is important to

distinguish between ends and means. It is also very important to make the means

serve the end, and not the other way around.

The end is the goal aimed at, the objective pursued.

The means is the processes, the methods, the acts that achieve the end or goal.

I want to make a table. That is my goal. I get planks,

I measure, I saw, I plane, I adjust, I nail the wood. These are the means, the

methods, which go into making the table.

All this is elementary. Yet, in the running of public

affairs, means are mistaken for the end, and the resulting chaos can be

amazing. For example, according to you, what is the goal, the end of economics:

A. To create jobs?

B. To reach a favourable balance of trade?

C. To distribute money to people?

D. To produce the goods that people need?

The correct answer is D. Yet, for practically all

politicians, the business of economics is to create jobs: but jobs are just a

means to produce goods, and goods are the real “end”. Today, thanks to the

heritage of progress, goods can be produced with ever-diminishing input of

human labour, and this leaves people ever-increasing free time to engage in

other activities, like looking after their families, or taking care of other

social duties. What would really be the point of continuing to produce

something when the need for it has already been satisfied? This would be just a

useless waste of resources. Now what about all those who cannot be employed in

the production system? The disabled, old people, children, housewives? Should

they starve to death? Not every human being is strictly a producer, but all

have needs, and are consumers.

To have a

favourable balance of trade means that you export to other countries more

products than you import from abroad, so you end up with less of your home

product, and are poorer in real wealth.

To have a

favourable balance of trade means that you export to other countries more

products than you import from abroad, so you end up with less of your home

product, and are poorer in real wealth.

To the question above, you might be tempted to answer

C, for is it not obvious that money is necessary to live today? Unless, that

is, if you produce all that you need yourself, but that is the exception in

today’s society, with the division of work where one person is the baker,

another one the carpenter, and so on, each one accomplishing a specific task

and producing specific goods.

Money is a means to obtain what is produced by others.

Note carefully, it is a means, not an end! You cannot eat money, wear it, or

put it on your feet. Money is there to buy food and clothing. First, these

things have to be produced and put on

sale in the market: money is not good if there is nothing you can buy with it.

What would be the use of having a million dollars in the North Pole or the

Let us not confuse “ends” with “means”; the same thing

applies to systems. The systems were invented and established to serve man, not

man created to serve systems. If a system is harmful to the mass of men, must

we let it continue, or do we not alter it to make serve the multitude? Another

question: since money is put there to oil the wheels of production and

distribution, must production and distribution be limited by the flow of money,

or, must money be made to flow in step with production and distribution?

Can you see now the error of

mistaking the ends for the means, and the means for the ends? Is this not a

silly, stupid and widespread error which causes much disorder in our society?

The purpose of economics

The word “economy” is derived from two Greek roots: Oikia, house; nomos,

rule.

Economy is therefore about the good regulation of a

house, of order in the use of the goods of the house.

Domestic economy is good management of domestic

affairs, and political economy is good management in the affairs of the large

communal home, the nation.

Management of the affairs of the small or large home, the

family or the nation, can be called “good” when it serves its purpose.

Man engages in different activities and pursues

different ends.

Man’s moral activities concern his final end.

Cultural activities affect the development of his

intellect, the ornamentation of his intellect, and the formation of his

character.

In participating in the general well-being of society,

man engages in social activities.

Economic activities deal with temporal wealth. In his

economic activities, man seeks to satisfy his temporal needs.

The goal, the purpose or end of economic activities,

is then the use of earthly goods to satisfy man’s temporal needs. Economics

serves its purpose when earthly goods serve human needs.

The temporal needs of man accompany him from the cradle

to the grave. Some needs are essential, others less so.

Hunger, thirst, bad weather, weariness, illness,

ignorance, create for man the need to eat, drink, clothe himself, find warmth,

shelter, refresh himself, rest, take care of his health, and to educate

himself.

These are all human needs.

Food, drink, clothing, shelter, wood, coal, water,

bed, remedies, the school teacher’s teaching books — all these things must be

present to meet man’s needs.

To have goods meet needs — this is the goal, the

purpose and end of economic life.

If it does this, economic life serves its end or

purpose. If it does not do this, or does it badly or incompletely, economic

life fails its purpose, or only meets that purpose imperfectly.

The goal is to join goods to needs, not only just to

bring them close together.

In straight terms, it may be said that economics is

good, that it serves its end, when it is sufficiently well-regulated for food

to enter the hungry stomach, for clothes to cover the naked body, for shoes to

protect the bare feet, for a good fire to warm the house in winter, for the

sick to receive the doctor’s visit, for teacher and the students to meet.

The purpose of economics is not only to produce goods;

these goods must be useful for people, answer their needs. Goods are not

produced to stay on the shelf, but to be consumed by the people who need them.

And for this to happen, people must have money to buy the goods that are on the

shelf in the store.

Economics has a purpose of its own: to satisfy man’s

needs. To eat when one is hungry is not the final goal, or end, of man; no, it

is only a means the better to aim towards his final goal, that is, to see God

face to face in Heaven for eternity.

If economics is only a means to the final end, if it

is only an intermediate end in the general order, it is nevertheless a very

distinctive end.

When economics join goods to needs, it is perfect. Let

us not ask more of it. But let us ask this of it. It is the purpose of

economics to achieve this perfect end, or goal.

Morality and economics

Let us not ask of economics to serve a moral purpose,

nor of morality to serve an economic purpose. This would be as disorderly as to

attempt to travel from

A starving man will not appease his hunger by reciting

his Rosary, but by eating food. This is in order. It is the Creator who wanted

it this way, and He turns from it only by departing from the established order,

through a miracle. He alone has the right to break this order. To satiate man’s

hunger, it is economics therefore that must intervene, not morality.

Similarly, a man who has a sullied conscience cannot

purify it by eating a good meal, or by drinking bucket loads of water. What he

needs is the confessional. In that case, it is religion’s place to intervene;

it is a moral activity, not an economic activity.

There is no doubt that morality must accompany all of

man’s actions, even in the domain of economics, but morality does not replace

economics. It guides in the choice of objectives, and it watches over the

legitimacy of the means, but it does not do what economics must do.

So, when economics does not meet its purpose, when

things stay in the stores or are not produced, and needs continue in the homes,

let us look for the cause in the economic order.

Let us blame, of course, those who disorganize the

economic order, or those who, having the mission to govern it, leave it in

anarchy. By not fulfilling their duties, they are certainly morally

responsible, and fall under the sanction of ethics.

If moral and ethics are truly distinct, both at the

same time concern the same man, and if the rules of one are broken, the other suffers.

Man has the moral duty to make sure that the economic order, the social

temporal order, serves its proper purpose.

Also, although economics is responsible only for the

satisfaction of man's temporal needs, the importance of good economic practices

has time and time again been stressed by those in charge of souls, because it

normally takes a minimum of temporal goods to encourage the practice of virtue,

as Saint Thomas Aquinas put it. We have a body and a soul, spiritual and

material needs. As the saying goes, “words are wasted on a starving man”, and

even the missionaries in poor countries know this. It is they who have to feed

the hungry before preaching to them. Man needs a minimum of goods to live his

short pilgrimage on earth and save his soul, but a money shortage can cause

terrible and inhuman situations. This is what brought Pope Benedict XV to

write, “It is in the economic field that the salvation of souls is at

stake.”

And Pius XI: “It may be said with all truth that

nowadays the conditions of social and economic life are such that vast

multitudes of men can only with great difficulty pay attention to that one

thing necessary, namely their eternal salvation.” (Encyclical Letter Quadragesimo Anno,

May 15, 1931.)

The social and very human end of

the economic organism is summed up in this sentence of Quadragesimo

Anno:

“Only

will the economic and social organism be soundly established and attain its

end, when it secures for each and all those goods which the wealth and

resources of nature, technical achievement, and the social organization of

economic affairs can give.”

EACH and ALL must be secured with all the goods that

nature and industry can provide.

The end and purpose of economics is therefore the

satisfaction of ALL of the consumers’ needs. The purpose is consumption;

production is only a means.

To make economics stop at production is to cripple it.

Economics must not finance production only; it must also finance consumption.

Production is the means, consumption is the end.

In an order where the end governs the means, it is man

as consumer who is in charge of all of the economy. And since every man is a

consumer, it is every man who contributes to ordering the production and

distribution of goods.

A really human economy is social, as we said; it must

satisfy ALL men. So EACH and ALL must be able to make their demands on the

production of goods — at least to satisfy their basic needs, as long as

production is in a position to respond to these demands.

The policy of a philosophy

Social Credit is not a utopia, but is based on a right

understanding of reality, on the just relationship between man and the society

in which he lives. As Clifford Hugh Douglas said, Social Credit is the policy

of a philosophy.

A policy is the action that we take, and it is based

on a conception of reality or, in other words, a philosophy.

Social Credit proclaims a philosophy which has existed

as long as men have lived in society, but which is terribly ignored in practice

— more than ever in this day and age.

This philosophy, as old as society itself — therefore

as old as the human race — is the philosophy of association. The social

teaching of the Church cal it: the common good.

The philosophy of association is therefore the joining

together of all associates for the good of the associates, of each associate.

Social Credit is the philosophy of association applied to general society, the

province, the nation. Society exists for the benefit of all the members of

society, for each and every one.

It is for this reason that Social

Credit is, by definition, the opposite of any monopoly: economic monopoly,

political monopoly, prestige monopoly, brutal-force monopoly.

Let us define Social Credit as a system of society at

the service of each and every one of its members, in which politics is at the

service of each and every one of the citizens, and economics is at the service

of each and every consumer.

Now let us define monopoly: the exploitation of the

social organization for the benefit of a few privileged individuals, where

politics is in the service of clans called parties, and economics works in the

service of a few financiers, a few ambitious and unscrupulous entrepreneurs.

Too often, those who condemn monopolies stop at

specified industrial monopolies: the electric monopoly, the coal monopoly, the

oil monopoly, the sugar monopoly, etc. They ignore the most pernicious of all

monopolies in the field of economics: the monopoly of money and credit; the

monopoly that transforms and subverts a country’s progress into public debts; a

monopoly which, by controlling the volume of money, regulates the human

standard of living, out of all relation to the realities of production and the

needs of families.

The aim of Social Credit is to “bind back to reality”

or “express in practical terms” in the current world, especially the world of

politics and economics, those beliefs about the nature of God and man and the

Universe which constitute the Christian Faith, as delivered to us from our

forefathers, and NOT as distorted and perverted to suit current politics or

economics, which stem from a non-Christian source.

Man lives in society, in a world subject to God’s

laws: the laws of nature (the physical laws of creation), and God’s moral law

(the Ten Commandments). The acceptance and knowledge of these laws implies

recognizing the consequences of violating them.

To accept Natural Law is to recognize that it is

inescapable reality, and that all people, as individuals or collectively in

society, are subject to Natural Law. Every event which occurs on the physical

plane is an abundant illustration of the laws of the physical universe. For

example, if a man jumps out of an aeroplane, he does not break the law of

gravity… he just illustrates, proves it. That observation is applicable to all

natural laws.

These laws are beyond the abrogation of man — they

cannot be disobeyed — the sanctions which enforce them are irresistible.

The chains (agreement associations — man made laws)

which individuals in society have forged for themselves — are optional, whereas

the Natural Law and its consequences are inescapable.

For example, money is a man-made system, not a system

created by God or by nature: it can be changed by man. The equilibrium of the

environment, however, has been created by God, and cannot be broken without

consequences. If we produce goods without respecting the environment, if we

pollute and waste the resources given to us by God, we have to suffer the

consequences.

The social credit: the confidence

that binds society together

![]()

In his booklet What is Social Credit?, Geoffrey

Dobbs wrote: “The social credit (without capital letters) is the name of

something, which exists in all societies but which never had a name before

because it was taken for granted. We become aware of it only as we lose it.

In his booklet What is Social Credit?, Geoffrey

Dobbs wrote: “The social credit (without capital letters) is the name of

something, which exists in all societies but which never had a name before

because it was taken for granted. We become aware of it only as we lose it.

“‘Credit’ is another word for ‘faith’ or ‘confidence’,

so we can also call it the Faith or Confidence which binds any society together

— the mutual trust or belief in each other without which fear is substituted

for trust as the “cement” of society... Though no society can exist without

some social credit, it is at its maximum where the Christian faith is

practised, and at its minimum where it is denied and derided.

“The social credit is thus a result, or practical

expression, of real Christianity in society, one of its most recognisable

fruits; and it is the aim and policy of social crediters

to increase it, and to strive to prevent its decrease. There are innumerable

commonplace examples of it which we take for granted every day of our lives.

How can we live in any sort of peace or comfort if we cannot trust our

neighbours? How could we use the roads if we could not trust others to observe

the rule of the road? (And what happens when they don’t!)

“What would be the use of growing anything in gardens,

farms or nurseries if other people were to grab it? How could any economic

activity go forward — whether producing, selling or buying — if people cannot,

in general, rely upon honesty and fair dealing? And what happens when the

concept of the Christian marriage, and the Christian family and upbringing, is

abandoned? We see, do we not? — that Christianity is something real with

desperately vital practical consequences, and by no means a mere set of

opinions which are ‘optional’ for those to whom they happen to appeal.”

You could add that without this respect for the social

credit, for the laws ruling society, any life in society would become

impossible, even though you put a police officer on every street corner, since

you could not trust anybody.

You could add that without this respect for the social

credit, for the laws ruling society, any life in society would become

impossible, even though you put a police officer on every street corner, since

you could not trust anybody.

Social Discredit

Mr. Dobbs continues:

“Just as there are social crediters, conscious

and unconscious, trying to build up the social credit (the confidence that we

can live together in society and benefit from it), so there are others — social

discrediters — trying to destroy it and break it

down, at present, with all too much success. The conscious ones include the

communists and other revolutionaries, who quite openly seek to smash all the

links of trust and confidence which enable our society to function until the

Day of the Revolution dawns... But it is the unconscious social discrediters who are responsible, in the West, for the

present success of the conscious ones....

“Why do shops and manufacturers foist upon us so many

shoddy, rubbishy, throw-away things, at outrageous prices, and trick us into

buying them with clever packaging and advertising? Why are most repair services

so scandalously slow, expensive and inefficient, and so many small services

which made life easier now unobtainable? And above all, why do millions of

decent working people of all classes take part in strikes deliberately designed

to damage services to their fellow men? What on earth can make normal decent

people descend to this spiritual level? We all know what it is. There is one

common factor running through all this destructive and discreditable action:

the compulsive need for more money to meet the ever-rising cost of living.

“So now at last I have come to the

question of money, which is what some people think that Social Credit is all

about; but it isn’t! Social Credit is an attempt to apply Christianity in

social affairs; but if money stands in the way, then we, and every Christian,

must concern ourselves with the nature of money, and just why it stands in the

way, as it surely does. There is a dire need for more people to look deeply

into the operation of our monetary system, though that is not everyone's job.

But when the consequences are so desperate, everyone can at least grasp the

outline of what is wrong, and could be put right, which will enable them to act

accordingly...”

LESSON 2 —

POVERTY AMIDST PLENTY

THE BIRTH AND DEATH OF MONEY

Do goods exist? Do they exist in sufficient quantity to

satisfy all of the consumers' basic needs?

Are we short of anything in our country to satisfy the

temporal needs of the citizens? Are we short of food for everybody to eat one’s

fill? Are we short of shoes, clothes? Can we not make as much as is required?

Are we short of railroads and other means of transportation? Are we short of

wood or stones to build good houses for all families? Are we short of builders,

manufacturers, or other workers? Are we short of machines?

No, we have all these things, in plenty. Never do the

retailers complain that they cannot find enough goods to meet the demand. Grain

elevators are bulging. Numerous are the able-bodied men waiting for work.

Numerous also are the machines which are at a standstill.

Yet, a great many people suffer! Goods are simply not

finding their way into homes.

Of what use is it to tell people that their country is

rich, that it exports a lot of goods, that it ranks third of fourth among the

world’s exporting countries?

What goes out of the country does not go into the

homes of the citizens. What sits idle in the stores does not appear on their

tables.

A mother does not feed her children or provide them

with shoes and garments, by going window-shopping, by reading the advertisements

of goods in newspapers, by listening to the description of good products on the

radio, or listening to the sales talk of countless salesmen of all kinds.

What is lacking is the effective means of laying hands

on these goods. You cannot steal them. To get them, you must pay for them: you

need money.

What is lacking is the effective means of laying hands

on these goods. You cannot steal them. To get them, you must pay for them: you

need money.

There are a lot of good things in our country, but

many individuals and families who need these goods lack the right to have them,

the permission to get them.

Is there anything lacking but money? What is lacking,

apart from the purchasing power to make the products go from stores to homes?

Mankind has gone through periods

of food shortage; famines covered big countries, and there was no appropriate

means of transportation to bring to these countries the wealth from other

sections of the planet. It is no longer the case today. There is an

overabundance of everything. It is abundance — no longer scarcity — that

creates the problem.

Mankind has gone through periods

of food shortage; famines covered big countries, and there was no appropriate

means of transportation to bring to these countries the wealth from other

sections of the planet. It is no longer the case today. There is an

overabundance of everything. It is abundance — no longer scarcity — that

creates the problem.

It is not at all necessary to go into detail to

demonstrate this fact. There are thousands of cases of voluntary destruction on

a large scale “to stabilize markets”, by making stocks disappear. Let us give

just a few examples:

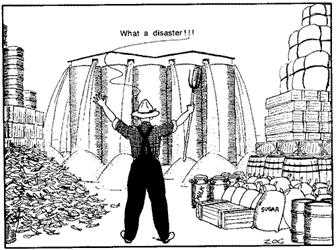

The

“The very same week this operation was taking place,

6,000 barrels of 200 pounds (90 kg) of herrings were dumped into the

Abundance is not confined to

“Public outrage has erupted over the European

Community’s (EC) plan to burn or dump in the ocean the huge surplus mountains

of butter, milk powder, beef and wheat piling up across EC nations. A report

from the EC’s

Why all this waste? Why don’t the products join the

needs? It is because people have no money. Wealth, goods are laughing in your

face and you starve in front of lofts full to overflowing, if you have got no

money. No money, no products: humans starve to death, and products are thrown

away.

Are we smarter than monkeys?

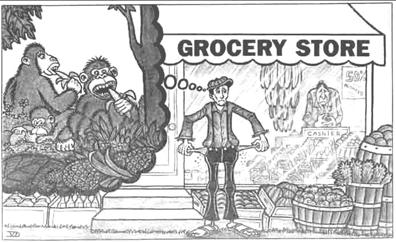

Look at the opposite cartoon: Here is a grocer's store

filled with good products in abundance; in front of this store, there is a

penniless starving man. Good products are made to be consumed. The grocer

displays them to sell them. The consumer would like to purchase them, but he

lacks the ticket to purchase them: he has got no money. The result: the good

products will not be consumed, and they will rot on the shelves. Yet, everybody

would be happier if the situation was different — the grocer would be happy to

sell, and the consumer would be happy to buy.

Look at the opposite cartoon: Here is a grocer's store

filled with good products in abundance; in front of this store, there is a

penniless starving man. Good products are made to be consumed. The grocer

displays them to sell them. The consumer would like to purchase them, but he

lacks the ticket to purchase them: he has got no money. The result: the good

products will not be consumed, and they will rot on the shelves. Yet, everybody

would be happier if the situation was different — the grocer would be happy to

sell, and the consumer would be happy to buy.

Why is it that something that would make everyone

happy cannot take place among human beings?

Let us have a

look at the monkeys. They see plenty of bananas on the banana trees. Since they

need to eat bananas to live, they simply pick the bananas and eat them.

Monkeys never worked out complicated economic systems

in their universities. In their heads of monkeys, they never examined the law

of supply and demand, nor the difference between socialism and neo-liberalism.

They simply saw good things in front of them, and they were smart enough to

pick them in order not to starve.

But a monkey is a monkey, and a man is a man. A monkey

has no mind, but a man can misuse his mind.

A monkey is led by its instinct, which does not

mislead it. Man is led by his mind, which is often misled by pride. In such a

case, man quibbles, uses dialectics, but forgets simple and pure reasoning

based on common sense.

This foolish situation of a multitude of starving

people amidst plenty of wealth is caused by the greed of those who base their

power on the bondage of the masses. You can say also that this foolish

situation is supported and maintained by people allegedly learned in economics,

who lead minds to the most stupid conclusions, under the pretence of reasoning

with science and wisdom.

This whole situation can also be summed up in the form

of a joke, although the conclusion is very serious: A group of monkeys in the

jungle were arguing whether men were more intelligent than monkeys. Some said

“yes”; others said “no”. One of the monkeys said: “To be clear in my own mind,

I will go to the city of the humans, and find out if they are really smarter

than us.” All the monkeys agreed that it was a good idea. So the monkey went,

and saw a penniless man starving in front of a grocery store filled with

bananas. The monkey came back to the jungle, and said to the other monkeys:

“Don't worry, men are not smarter than us; they starve to death in front of

bananas that rot on the shelves for lack of money.”

Conclusion: Let's be smarter than the monkeys, and let

us devise a money system that will allow us to eat the bananas and all the

other products that are provided in plenty by God for all His children. This

smart money system exists; it is Social Credit.

Money and

wealth

We have just shown that what is lacking is not

products, but money. This does not mean that money itself is wealth. Money is

not an earthly good capable of satisfying a temporal need. As we said in the

previous lesson, money is a means, the end is the products.

You cannot keep yourself alive by eating money. To get

dressed, you cannot sew together dollar bills to make a dress or a pair of

stockings. You cannot rest by lying down on money. You cannot cure a sickness

by putting money on the seat of the malady. You cannot educate yourself by

crowning your head with money.

Money is not real wealth. Real wealth consists of all

the useful things which satisfy human needs.

Bread, meat, fish, cotton, wood, coal, a car on a good

road, a doctor visiting the sick, the knowledge of a science — these are real

wealth.

In our modern world, each individual does not produce

all things. People must buy from one another. Money is the symbol or token that

you get in return for a thing sold; it is the symbol that you must give in

return for a thing that you want from another.

Wealth is the thing; money is the symbol of that

thing. The symbol should reflect the thing.

If there are a lot of things for sale in a country,

there must be a great deal of money to dispose of them. The more people and

goods, the more money in circulation is required, otherwise everything stops.

It is precisely this balance that is lacking today. We

have at our disposal almost as great a quantity of goods as we could possibly

wish, thanks to applied science, to new discoveries, and to the perfecting of

machinery. We even have a lot of people without occupations, who represent a potential

source of goods. We have loads of useless, even pernicious, occupations. We

have activities of which the sole end is destruction.

Money was created for the purpose of keeping goods

moving. Why, then, does it not find its way into the hands of the people in the

same measure as the flow of goods from the production line?

Money

begins somewhere

Everything, except God, has a beginning. Money is not

God, therefore it has a beginning. Money begins somewhere.

Everything, except God, has a beginning. Money is not

God, therefore it has a beginning. Money begins somewhere.

We know the origin of such useful commodities as food,

clothing, shoes, books. Workers, machines, plus the country’s natural

resources, produce the wealth, the goods we need and which we do not lack.

But then where does money begin, the money that we

lack in order to buy the goods that are not lacking?

The first idea that we keep alive in our minds,

without really realizing it, is that there is one fixed quantity of money, and

that it cannot be changed; as if it was the sun, or the rain, or the weather.

This idea is utterly wrong; if there is money, it is because it was made

somewhere. If there is not more, it is because those who made it did not make

more.

Another prevalent belief about the origin of money is

that the Government makes it. This is also incorrect. The Government today does

not create money, and complains continuously about not having any. If the

Government were the source of money, it would not have sat around idly for ten

years in front of the lack of money. (And for example, in

Now, we will explain where money begins and ends.

Those who control the birth and death of money also regulate its volume. If

they make much money and destroy little, there is more. If the destruction of

money goes faster than its creation, its quantity decreases.

Our standard of living, in a country where money is

lacking, is not regulated by the volume of goods produced, but by the amount of

money at our disposal to buy these goods. So those who control the volume of

money, control our standard of living. “Those who control money and credit

have become the masters of our lives... No one dare breathe against their

will.” (Pope Pius XI, Encyclical Letter Quadragesimo

Anno).

Two kinds of

money

Money is whatever serves to pay, to buy; whatever is

accepted in exchange for goods or services.

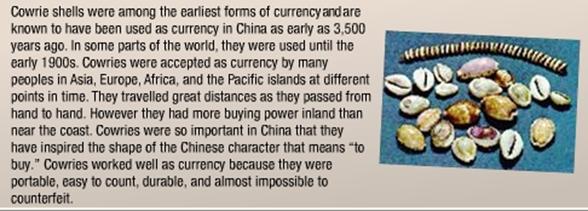

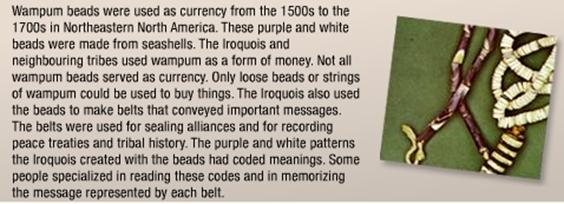

The material substance of which money is made is of no

importance. In the past, money has at times been made of shells, shark teeth,

leather, wood, iron, silver, gold, copper, paper, etc.

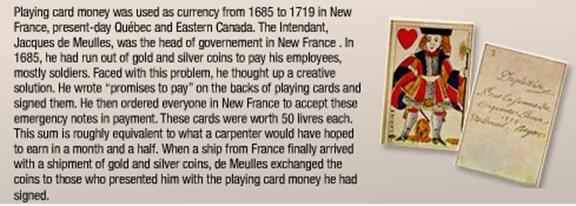

Examples

of money in the past

Source:

http://www.currencymuseum.ca/eng/learning/digit.php

There are at present two kinds of money in

Book money is the bank account. Business operates

through bank accounts. Whether pocket money circulates or not depends on the

state of business. But business does not depend upon pocket money; it is kept

going by the bank accounts of businessmen.

Book money is the bank account. Business operates

through bank accounts. Whether pocket money circulates or not depends on the

state of business. But business does not depend upon pocket money; it is kept

going by the bank accounts of businessmen.

With a bank account, payments or purchases are made

without using metal or paper money. Buying is done only with figures.

Let us suppose I have a bank account of $40,000. I buy

a car worth $10,000. I make my payment by writing a cheque. The car dealer

endorses the cheque, and deposits it at his bank.

The banker then makes changes in two accounts: first,

that of the car dealer, which he increases by $10,000; then mine, which he

decreases by $10,000. The car dealer had $500,000 — he now has $510,000 written

in his bank account. I had $40,000 in mine — my bank account now shows $30,000.

Paper money did not move in the country because of

this deal. I simply gave some figures to the car dealer. I paid with figures.

More than nine-tenths of all business is done this way.

It is book money, the money made of figures, which is modern money; it is the

most abundant money; its volume is ten times that of paper or metal money. It

is a superior type of money, since it gives wings to the other. It is the

safest kind of money, the one that no one can steal.

Savings and borrowing

Book money, like the other type of money, has a

beginning. Since book money is a bank account, it comes into existence when a

bank account is opened without money decreasing anywhere, neither in another

bank account nor in anyone's pocket.

Book money, like the other type of money, has a

beginning. Since book money is a bank account, it comes into existence when a

bank account is opened without money decreasing anywhere, neither in another

bank account nor in anyone's pocket.

The amount in a bank account can be increased in two

ways: by saving and by borrowing. There are other ways, but they can be

classified under borrowing.

The savings account is a transformation of money. I

bring along some pocket money to the banker; he increases my account by this

amount. I no longer have that pocket money; I have book money at my disposal. I

can get back pocket money by decreasing the amount of book money in my account.

It is a simple transformation of money.

But since we are trying to find out how money comes

into existence, the savings account, being a simple transformation of money, is

of no interest to us here.

Money

begins in the banks

Money

begins in the banks

The borrowing (or loan) account is the account lent by

the banker to a borrower. Let us suppose I am a businessman. I want to set up a

new factory. All I need is money. I go to a bank and borrow $100,000 under

security. The banker makes me sign a promise to pay back the amount with

interest. Then he lends me the $100,000.

Is he going to hand me the $100,000 in paper money? I

do not want it. First, it is too risky. Furthermore, I am a businessman who

buys things at different and widely far-flung places, through the medium of

cheques. What I want is a bank account of $100,000 which will make it easier

for me to carry on business.

The banker will therefore lend me an account of

$100,000. He will credit my account with $100,000, just as if I had brought

that amount to the bank. But I did not bring it; I came to get it.

Is it a savings account, set up by me? No, it is a

borrowing account made by the banker himself, for me.

Money

creators

Money

creators

This account of $100,000 was made, not by me, but by

the banker. How did he make it? Did the amount of money in the bank decrease

when the banker lent me $100,000? Well, let us ask the banker:

— Mr. Banker, have you any less money in your vault

after having lent me $100,000?

— I haven't gone into my vault.

— Have other people's accounts been reduced?

— They remain exactly as they were.

— Then what was decreased in the bank?

— Nothing was decreased.

— Yet my account has been increased. From where did

the money you lent me come?

— It didn't come from anywhere.

— Where was it when I came into the bank?

— It didn't exist.

— And now that it is in my account, it exists. So we

can say that it was created.

— Certainly.

— Who created it, and how?

— I did, with my pen and a drop of ink when I

inscribed $100,000 to your credit, at your request.

— Then you create money?

— The banks create book money, the money of figures.

That's the modern money that puts into circulation the other type of money by

keeping business on the move.

The banker manufactures money, ledger money, when he

lends accounts to borrowers, individuals, or governments. When I leave the

bank, there will exist in this country a new source of cheques, one that did

not exist before. The total amount of all accounts in the country was increased

by $100,000. With this new money, I will pay the workers, buy materials and

machinery — in short, build my new factory. Who, then, creates money? — The

bankers!

LESSON 3 — BANKS CREATE MONEY AS A

DEBT

Fractional banking system — The

goldsmith who became a banker

In the example of the previous lesson, when I was

granted a $100,000 loan, the banker actually created $100,000 of new money in

the form of credit, in the form of bookkeeping money, which is just as good as

coins and paper money.

The banker is not afraid to do this. My cheques to

payees will give them the right to draw money from the bank. But the banker

knows very well that nine-tenths of these cheques will simply have the effect

of decreasing the money in my account, and of increasing it in other people's

accounts. He knows very well that a ratio of bank reserves to deposits of 1/10

is enough for him to meet the requests of those who want pocket money. In other

words, the banker knows very well that if he has $10,000 in cash reserves, he

can lend $100,000 (ten times the sum) in bookkeeping money.

In technical terms, the capacity for a bank to lend 10

times the amount of paper money it has in its safe is called fractional banking

system. The origin of this system goes back to the Middle Ages. It is the true

story of the goldsmiths who became bankers, as told now by Louis Even:

If you have some imagination, go back a few centuries

to a  purchase foreign products.

purchase foreign products.

However, the wars between lords or nations, and armed

robberies, were causing the gold and the diamonds of the wealthy to fall into

the hands of pillagers. So the owners of gold, who had become very nervous,

made it a habit to entrust their treasures for safekeeping to the goldsmiths

who, because of the precious metal they worked with, had very well protected

vaults. The goldsmith received the gold, gave a receipt to the depositor, and

took care of the gold, charging a fee for this service. Of course, the owner

claimed his gold, all or in part, whenever he felt like it.

The merchant leaving for Paris or Marseille, or

travelling from

It also happened that the supplier, in

Instead of the gold, it was the goldsmith's receipts

which were changing hands. For as long as there were only a limited number of

sellers and buyers, it was not a bad system. It was easy to follow the journey

of the receipts.

The gold lender

The goldsmith soon made a discovery, which was to

affect mankind far more than the memorable journey of Christopher Columbus

himself. He learned, through experience, that nearly all of the gold that was

left with him for safekeeping remained untouched in his vault. Barely more than

one-in-ten of the owners of this gold ever took it out of the vault to conduct

their business transactions, using their receipts instead for the purpose.

The thirst for gain, the longing to become rich faster

than by means of the jeweller’s tools, sharpened the mind of our man, and he

made a daring gesture. “Why,” he said to himself, “would I not become a gold

lender!” A lender, mind you, of gold which did not belong to him. And since he

did not possess a righteous soul like that of Saint Eligius

(or St. Eloi, the master of the mint of French kings Clotaire II and Dagobert I, in

the seventh century), he hatched and nurtured the idea. He refined the idea

even more: “To lend gold which does not belong to me, at interest, needless to

say! Better still, my dear master (was he talking to Satan?), instead of the

gold, I will lend a receipt, and demand payment of interest in gold; that gold

will be mine, and my clients' gold will remain in my vaults to back up new

loans.”

The thirst for gain, the longing to become rich faster

than by means of the jeweller’s tools, sharpened the mind of our man, and he

made a daring gesture. “Why,” he said to himself, “would I not become a gold

lender!” A lender, mind you, of gold which did not belong to him. And since he

did not possess a righteous soul like that of Saint Eligius

(or St. Eloi, the master of the mint of French kings Clotaire II and Dagobert I, in

the seventh century), he hatched and nurtured the idea. He refined the idea

even more: “To lend gold which does not belong to me, at interest, needless to

say! Better still, my dear master (was he talking to Satan?), instead of the

gold, I will lend a receipt, and demand payment of interest in gold; that gold

will be mine, and my clients' gold will remain in my vaults to back up new

loans.”

He kept the secret of his discovery to himself, not

even talking about it to his wife, who wondered why he often rubbed his hands

in great glee. The opportunity to put his plans into operation did not take

long in coming, even though he did not have “The Globe and Mail” or “The

Toronto Star” in which to advertise.

One morning, a friend of the goldsmith actually came

to see him and asked for a favour. This man was not without goods — a home, or

a farm with arable land — but he needed gold to settle a transaction. If he

could only borrow some, he would pay it back with an added surplus; if he did

not, the goldsmith would seize his property, which far exceeded the value of

the loan.

The goldsmith got him to fill out a form, and then

explained to his friend, with a disinterested attitude, that it would be

dangerous for him to leave with a lot of money in his pockets: “I will give you

a receipt; it is just as if I were lending you the gold that I keep in reserve

in my vault. You will then give this receipt to your creditor, and if he brings

the receipt to me, I will in turn give him gold. You will owe me so much

interest.”

The creditor generally never showed up. He rather

exchanged the receipt with someone else for something that he required. In the

meantime, the reputation of the gold lender began to spread. People came to

him. Thanks to other similar loans by the goldsmith, soon there were many times

more receipts in circulation than real gold in the vaults.

The goldsmith himself had really created a monetary

circulation, at a great profit to himself. He quickly lost the original

nervousness he had when he had worried about a simultaneous demand for gold

from a great number of people holding receipts. He could, to a certain extent,

continue with his game in all safety. What a windfall; to lend what he did not

have and get interest from it, thanks to the confidence that people had in him

— a confidence that he took great care to cultivate! He risked nothing, as long

as he had, to back up his loans, a reserve that his experience told him was

enough. If, on the other hand, a borrower did not meet his obligations and did

not pay back the loan when due, the goldsmith acquired the property given as

collateral. His conscience quickly became dulled, and his initial scruples no

longer bothered him.

The creation of credit

Moreover, the goldsmith thought it wise to change the

way his receipts were set out when he made loans; instead of writing, “Receipt

of John Smith...” he wrote, “I promise to pay to the bearer...”. This promise

circulated just like gold money. Unbelievable, you will say? Come on now, look

at your dollar bills of today. Read what is written on them. Are they so

different, and do they not circulate as money?

A fertile fig tree — the private banking system, the

creator and master of money — had therefore grown out of the goldsmith's

vaults. His loans, without moving gold, had become the banker's creations of

credit. The form of the primitive receipts had changed, becoming that of simple

promises to pay on demand. The credits paid by the banker were called deposits,

which caused the general public to believe that the banker loaned only the

amounts coming from the depositors. These credits entered into circulation by

means of cheques issued on these credits. They displaced, in volume and in

importance, the legal money of the Government which only had a secondary role

to play. The banker created ten times as much paper money as did the State.

The goldsmith who became a banker

The goldsmith, transformed into a banker, made another

discovery: he realized that putting plenty of receipts (credits) into

circulation would accelerate business, industry, construction; whereas

restriction of credits, which he practised at first in circumstances in which

he worried about a run on the bank for gold, paralyzed business development.

There seemed to be, in the latter case, an overproduction, when privations were

actually great; it is because the products were not selling, due to a lack of

purchasing power. Prices went down, bankruptcies increased, the banker's

debtors could not meet their obligations, and the lenders were seizing the

properties given as collateral. The banker, very clear-sighted and very skillful when it came to gain, saw his opportunities, his

marvellous opportunities. He could monetize the wealth of others for his own

profit: by doing it liberally, causing a rise in prices, or parsimoniously,

causing a decrease in prices. He could then manipulate the wealth of others as

he wished, exploiting the buyer in times of inflation, and exploiting the

seller in times of recession.

The banker, the universal master

The banker thus became the universal master, keeping

the world at his mercy. Periods of prosperity and of depression followed one

another. Humanity bowed down before what it thought were natural and inevitable

cycles.

Meanwhile, scholars and technicians tried desperately

to triumph over the forces of nature, and to develop the means of production.

The printing press was invented, education became widespread, cities and better

housing developed. The sources of food, clothing, and comforts increased and were

improved. Man overcame the forces of nature, and harnessed steam and

electricity. Transformation and developments occurred everywhere — except in

the monetary system.

And the banker surrounded himself with mystery,

keeping alive the confidence that the captive world had in him, even being so

audacious as to advertise in the media, of which he controlled the finances;

that the bankers had taken the world out of barbarism, that they had opened and

civilized the continents. The scholars and wage-earners were considered but

secondary in the march of progress. For the masses, there was misery and

contempt; for the exploiting financiers, wealth and  honours!

honours!

The ratio of cash versus loans in Canadian banks was

about one for ten in the 1940s. This ratio (a 10% cash reserve requirement) has

changed since then. In 1967, the Canadian Bank Act allowed the chartered banks

to create sixteen times (in bookkeeping money) the sum of their cash reserves.

Beginning in 1980, the minimum reserve required in cash (bank notes and coins)

was 5 per cent, which meant that the banker needed only one dollar out of

twenty to answer the needs of those who wanted pocket money. The banker knew

very well that if he had $10,000 in cash, he could lend twenty times the sum,

or $200,000, in bookkeeping money.

In practice, the banks could lend out even more than

that, since they could increase their cash reserves at will by simply

purchasing bank notes from the central bank (the Bank of Canada) with the

bookkeeping money they create out of thin air, with a pen. For example, it was

established in 1982, before a parliamentary committee on bank profits, that in

1981, the Canadian chartered banks, as a whole, made loans 32 times in excess

of their combined capital. A few banks even lent sums equal to 40 times their

capital. Moreover, in 1990 in the

Subsection 457(1) of the most recent version of the

Canadian Bank Act, enacted on

Money destroyers

So we have just seen that banks create money when they

make a loan, as it was explained at the end of the previous lesson: The banker

manufactures money, ledger money, when he lends accounts to borrowers,

individuals, or governments. When I leave the bank, there will exist in this

country a new source of cheques, one that did not exist before. The total

amount of all accounts in the country was increased by $100,000. With this new

money, I will pay the workers, buy materials and machinery — in short, build my

new factory. Who, then, creates money? — The bankers!

The bankers, and the bankers alone, make this kind of

money: bank money, the money that keeps business moving. But they do not give

away the money they create. They lend it. They lend it for a certain period of

time, after which it must be returned to them. The bankers must be repaid.

The bankers claim interest on this money that they

have created. In the case mentioned in the previous lesson, with a

$100,000-loan, the banker will probably demand $10,000 from me in interest, at

once. He will withhold it from the loan, and I will leave the bank with $90,000

in my account, having signed a promise to repay $100,000 in one year's time.

In building my factory, I will pay my men, buy things,

and thus spread my bank account of $90,000 throughout the country. But within a

year, I must, through the profits I make selling my goods for more than they

cost me, build my account up to not less than $100,000.

At the end of the year, I will pay back the loan by

making out a cheque for $100,000 on my account. The banker will then debit my

account by $100,000, therefore taking from me this $100,000 I have drawn from

the country by selling my goods. He will not put this money into the account of

anyone. No one will be able to draw cheques on this $100,000. It is dead money.

Borrowing

gives birth to money. Repayment brings about its extinction. The bankers bring

money into existence when they make a loan. The bankers send money to the grave

when they are repaid. The bankers are therefore also destroyers of money.

Borrowing

gives birth to money. Repayment brings about its extinction. The bankers bring

money into existence when they make a loan. The bankers send money to the grave

when they are repaid. The bankers are therefore also destroyers of money.

As a distinguished British banker, the Right

Honourable Reginald McKenna, one-time British Chancellor of the Exchequer, and

Chairman of the Midland Bank, one of the Big Five (five largest banks of

England), said: “Every loan, overdraft, or bank purchase creates a deposit, and

every repayment of a loan, overdraft, or bank sale destroys a deposit.”

![]() And the system so operates that the repayment must be

greater than the original loan; the death figures must exceed the birth

figures; the destruction must exceed the creation.

And the system so operates that the repayment must be

greater than the original loan; the death figures must exceed the birth

figures; the destruction must exceed the creation.

This seems impossible, and collectively, it is impossible. If I succeed,

someone else must go bankrupt, because, all together, we are not able to repay more

money than has been made. The bankers create nothing but the capital sum. No

one creates what is necessary to make up the interest, because no one else

creates money. And yet, the bankers demand both capital and interest. Such a

system cannot hold out except for a continuous and ever-increasing flow of

loans. Hence the system of debts, and the strengthening of the dominating power

of the banks.

The national debt

The Government does not create money. When the

Government can no longer tax nor borrow from individuals, due to the scarcity

of money, it borrows from the banks.

The operation takes place exactly like mine. As a

guarantee, it pledges the whole country. The promise to pay back is the

debenture. The loan of the money is an account made by a pen and some ink.

Thus, in October, 1939, the federal government, in

order to cover the initial expenses of the war, asked some $80,000,000 from the

banks. The banks lent the government an account of $80 million without taking a

cent from anyone, thus giving the government a new base for cheques of $80

million. But, in October, 1941, the government had to repay $83,200,000 to the

banks, including both capital and the interest.

Through taxes, the government had to remove from the

country as much money as it had spent, $80 million, but, in addition, it had to

draw from the country a further $3 million, money it had not put into the

country, which had neither been made by the bankers nor by anyone else.

Even conceding at the most that the government can

find the money that exists, how can it find the money that has never been

created? The plain fact is, the government does not find it. It is simply added

to the national debt. This explains why the national debt increases in the same

measure as the country’s development requires more money. All new money comes

into existence as a debt, through the banker, who claims more money than he has

actually issued.

And the country's population finds itself collectively

indebted for a production that, collectively, it made itself! It is the case

for war production. It is the case also for peacetime production: roads,

bridges, waterworks, schools, churches, etc.

The

monetary defect

The situation comes down to this inconceivable thing:

all the money in circulation comes only from the banks. Even metal and paper

money comes into circulation only if it has been released by the banks.

Now the banks put money into circulation only by

lending it out at interest. This means that all the money in circulation comes

from the banks, and must someday be returned to the banks, increased with the

interest.

The banks remain the owners of the money. We are only

the borrowers. If some manage to hang on to their money for a long period of

time, or even permanently, others are necessarily incapable of fulfilling their

financial commitments.

A multiplicity of bankruptcies, both for individuals

and companies, mortgage upon mortgage, and an ever-increasing public debt, are

the natural fruits of such a system.

Claiming an interest on money as it comes into

existence is both illegitimate and absurd, antisocial and contrary to good

arithmetic. The monetary defect is therefore as much a technical defect as a

social defect.

As the country is developed, in production as well as

in population, more money is needed. But it is impossible to get new money

without contracting a debt which, collectively, cannot be paid.

So we are left with the alternatives of either

stopping developments or getting into debt; of either plunging into mass

unemployment or into an unrepayable debt. And it is

precisely this dilemma that is being debated in every country.

Aristotle, and after him, Saint Thomas Aquinas, wrote

that money does not breed more money, but the banker brings money into

existence only on the condition that it breeds more money. Since neither

governments nor individuals create money, no one creates the interest claimed

by the banker. Even if legalized, this form of issue remains vicious and

insulting.

Decline

and degradation

This way of making the country's money, by forcing

governments and individuals into debt, establishes a real dictatorship over

governments and individuals alike.

The sovereign Government has become a signatory of

debts to a small group of profiteers. A minister, who represents millions of

men, women and children, signs unpayable debts. The

bankers, who represent a clique interested only in profit and power,

manufacture the country's money.

Without blood, humans cannot survive; so it is fair to

compare money with the economic lifeblood of the nation. Pope Pius XI wrote in

1931, in his encyclical letter Quadragesimo

Anno: “This power becomes particularly

irresistible when exercised by those who, because they hold and control money,

are able also to govern credit and determine its allotment, for that reason

supplying, so to speak, the lifeblood to the entire economic body, and

grasping, as it were, in their hands the very soul of production, so that no

one dare breathe against their will.”

Without blood, humans cannot survive; so it is fair to

compare money with the economic lifeblood of the nation. Pope Pius XI wrote in

1931, in his encyclical letter Quadragesimo

Anno: “This power becomes particularly

irresistible when exercised by those who, because they hold and control money,

are able also to govern credit and determine its allotment, for that reason

supplying, so to speak, the lifeblood to the entire economic body, and

grasping, as it were, in their hands the very soul of production, so that no

one dare breathe against their will.”

A few lines further, the Pope spoke of the

degeneration of power that ensues, saying that governments have surrendered

their noble functions, and have become the servants of private interests.

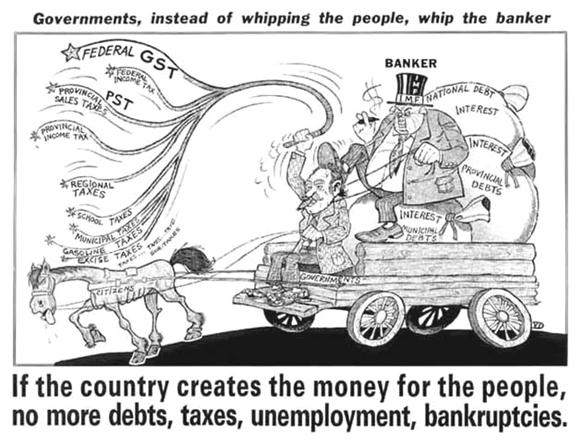

The government, instead of guiding the State, has

become a mere tax collector; and a great slice from tax revenues, the most

sacred slice, kept above all discussion, is purely and solely for the interest

on the national debt.

Furthermore, the legislation consists, above all, in

taxing people and setting up, everywhere, restrictions on freedom.

There are laws to ensure that the money creators are

repaid. There are no laws to prevent a human being from dying of extreme

poverty.

As for individuals, the scarcity of money develops a

mentality of wolves. In the face of plenty, only those who have money — the too

scarce symbol of goods — are given the right to draw on that plenty. Hence the

counterproductive competition, the tyranny of the “boss”, domestic strife, etc.

A small number preys on all the others. The great mass

of the people groan, many in the most degrading poverty.

The sick remain without care; children are poorly or

insufficiently nourished; talents go undeveloped; youths can neither find a job

nor start a home or family; farmers lose their farms; industrialists go

bankrupt; families struggle along with difficulty — all this without any other

justification than the lack of money. The banker’s pen imposes privations on

the people, servitude on the governments.

With all this said, a striking point must be

emphasized: It is production that gives value to money. A pile of money without

corresponding products does not keep anyone alive, and is absolutely worthless.

Thus, it is the farmers, the industrialists, the workers, the professionals,

the organized citizenry, who make products, goods and services. But it is the

bankers who create the money, based on these products. And the bankers

appropriate this money, which draws its value from the products, and lend it to

those who make the products.

A debt-money system: The Money Myth

Exploded

A debt-money system: The Money Myth

Exploded

The way money is created by private banks as a debt is

well explained in Louis Even’s parable, The Money

Myth Exploded, in which the economic system is clearly divided into two parts:

the producing system and the financial system. So, on the one side, there are

five shipwrecked people on an island, who produce all the necessities of life,

and on the other side, a banker, who lends them money. To simplify this

example, let us say there is only one borrower on behalf of the community;

we'll call him Paul.

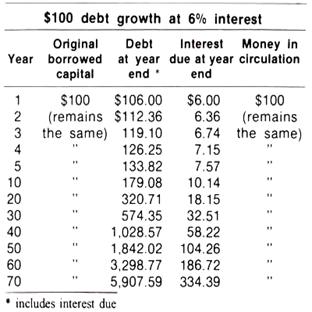

Paul decides, on behalf of the community, to borrow a

certain amount of money from the banker, an amount sufficient for business in

the little community, say $100, at 6% interest. At the end of the year, Paul

must pay the bank an interest of 6%, that is to say, $6. 100 minus 6 = 94, so

there is $94 left in circulation on the island. But the $100-debt remains. The

$100-loan is therefore renewed for another year, and another $6 of interest is

due at the end of the second year. 94 minus 6, leaves $88 in circulation. If

Paul continues to pay $6 in interest each year, by the seventeenth year there

will be no more money left in circulation on the island. But the debt will

still be $100, and the banker will be authorized to seize all the properties of

the island's inhabitants.

Production has increased on the island, but not the

money supply. It is not products that the banker wants, but money. The island's

inhabitants were making products, but not money. Only the banker has the right

to create money. So, it seems that Paul wasn't wise to pay the interest yearly.

Let us go back to the beginning of our example. At the

end of the first year, Paul chooses not to pay the interest, but to borrow it

from the banker, thereby increasing the loan principal to $106. “No problem,”

says the banker, “the interest on the additional $6 is only 36 cents; it is

peanuts in comparison with the $106 loan!” So the debt at the end of the second

year is: $106 plus the interest at 6% of $106, $6.36, for a total debt of

$112.36 after two years. At the end of the fifth year, the debt is $133.82 and

the interest is $7.57. “It is not so bad,” thinks Paul, “the interest has only

increased by $1.57 in five years. We can handle that.” But what will the

situation be like after 50 years?

Let us go back to the beginning of our example. At the

end of the first year, Paul chooses not to pay the interest, but to borrow it

from the banker, thereby increasing the loan principal to $106. “No problem,”

says the banker, “the interest on the additional $6 is only 36 cents; it is

peanuts in comparison with the $106 loan!” So the debt at the end of the second

year is: $106 plus the interest at 6% of $106, $6.36, for a total debt of

$112.36 after two years. At the end of the fifth year, the debt is $133.82 and

the interest is $7.57. “It is not so bad,” thinks Paul, “the interest has only

increased by $1.57 in five years. We can handle that.” But what will the

situation be like after 50 years?

The debt increase is moderate in the early years, but

the debt increases very fast with time to unbelievably big numbers. And note,

the debt increases each year, but the original borrowed principal (amount of

money in circulation) always remains the same. At no time can the debt be paid

off with the money that exists in circulation, not even at the end of the first

year: there is only $100 in circulation, and a debt of $106 remains. And at the

end of the fiftieth year, all the money in circulation ($100) won't even pay

the interest due on the debt: $104.26.

All money in circulation is a loan and must be

returned to the bank, increased with interest. The banker creates money and

lends it, but he has the borrower's pledge to bring all this money back, plus

other money he did not create. Only the banker can create money: he creates the

principal, but not the interest. And he demands that we pay him back, in

addition to the principal that he created, the interest that he did not create,

and that nobody else created either. As it is impossible to pay back money that

does not exist, debts accrue. The public debt is made up of money that does not

exist, that has never been created, but that governments nevertheless have

committed themselves to paying back. An impossible contract, represented by the

bankers as a “sacrosanct contract”, to be abided by, even though human beings

die because of it.

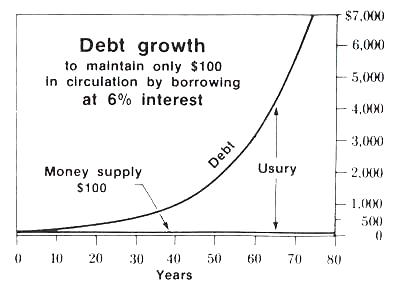

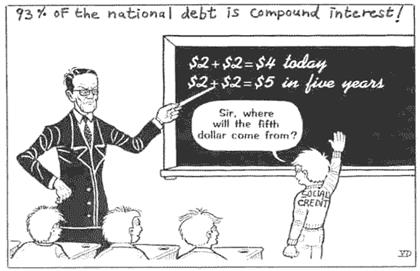

Compound interest

The sudden increase in the debt after a certain number

of years can be explained by the effect of what is called compound interest.

Contrary to simple interest, which is paid only on the original borrowed

capital, compound interest is paid on both the principal plus the accumulated

unpaid interest. Thus, with simple interest, a $100-loan at 6% interest would

give, at the end of 5 years, a debt of $100 plus 5 times 6% of $100 ($30.00),

for a total debt of $130. But with compound interest, the debt at the end of

the fifth year is the sum of the debt of the previous year ($126.35) plus 6%

interest of this amount, for a total debt of $133.82.

Put all these results on a chart: the horizontal line

across the bottom of the chart is marked off in years, and the vertical line is

marked off in dollars. Connect all these points by a line we trace a curve, and

you see the effect of compound interest and the growth of the debt:

Put all these results on a chart: the horizontal line

across the bottom of the chart is marked off in years, and the vertical line is

marked off in dollars. Connect all these points by a line we trace a curve, and

you see the effect of compound interest and the growth of the debt:

The curve is quite flat at the beginning, but then

becomes steeper as time goes on. The debts of all countries follow the same

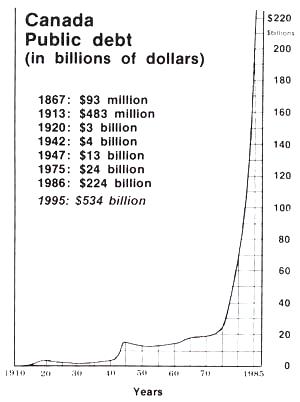

pattern, and are increasing in the same way. Let us study, for example,

Canada

Each year, the Canadian Government draws up a budget

wherein are estimated the expenditures and the revenues for the year. If the

Government takes in more money than it spends, there is a surplus; if it spends

more than it takes in, there is a deficit. Thus, for the fiscal year 1985/86

(the Government's fiscal year runs from April 1 to March 31), the Federal

Government had expenditures of $105 billion and revenues of $71.2 billion,

leaving a deficit of $33.8 billion. This deficit represents a deficiency in

revenues. (The Federal Debt has managed to balance its budget over the recent

years, but it is simply because it downloaded its deficit on provinces and

municipalities, forcing them to make cuts in health and other basic services.

This does not prevent the overall debt of all public administrations from

continuing to increase.) The national debt is the total accumulation of all

budgetary deficits since

When

When

But how can be explained the phenomenal increase of

these last years, when the debt almost increased ten times, passing from $24

billion in 1975 to $224 billion in 1986, in peacetime, when

It is the effect of compound interest, like in

the example of the island in The Money Myth Exploded. The debt increases slowly

in the early years, but grows extremely fast in the following years. And

Here is another explanation for

There is a big difference between interest rates of

6%, 10%, or 20%, when you speak of compound interest. The following are the

sums that $1.00 will amount to in 100 years, loaned at the rates of interest

shown and compounded annually:

at

1%............................$2.75

at 2%..........................$19.25

at 3%........................$340.00

at 10%..................$13,809.00

at 12%............ $1,174,406.00

at 18%............$15,145,207.00

at 24%..........$251,799,494.00

And at 50%, it would eat up the world! There is a

formula to calculate approximately the amount of time it will take for an

amount, at compound interest, to double; it is the “Rule of 72”: You divide 72

by the interest rate. It gives you the number of years it will take for the

amount to double. Thus, an interest rate of 10% will cause a loan to double in

7.2 years (72 divided by 10).

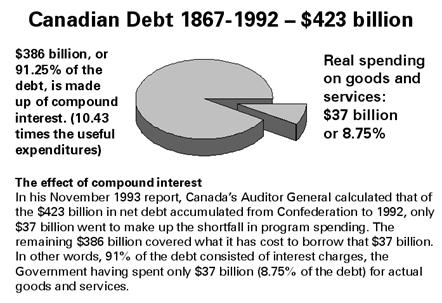

All this is to show that any interest demanded on money created out of

nothing, even at a rate of 1%, is usury. In his November 1993 report,

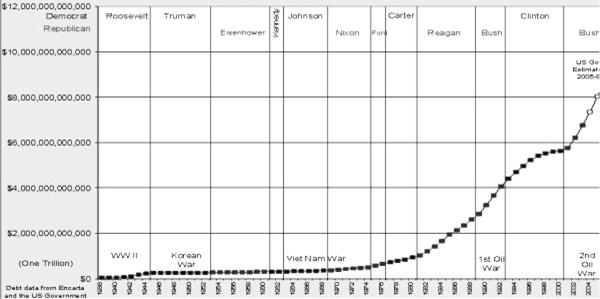

The public

debt of the United

States

The public debt of the

In October 2005, the federal debt reached the $8

trillion mark ($26,672 for each

In October 2005, the federal debt reached the $8

trillion mark ($26,672 for each

LESSON