The Credits required to finance production and distribution would be drawn from the country’s Financial Credit which is based on the country’s tremendous Real Credit.

No major changes need to be made to the existing structures. Private businesses would remain privately owned. Banks could remain private businesses as they presently are. It is through banks that Financial Credit would be issued.

Banks now possess all that is needed: the equipment. a well-established network of branches and a well trained and competent staff to conduct this service efficiently. Banks could continue to be rewarded for their services. They could continue to be responsible for the loans granted for production and for the accounting operations related to consumer credit [the Dividend and Compensated Discount] and receive proper remuneration for doing so. But the Credit managed by the banks would remain the property of society and their different operations would have to abide by the objectives set by a financial system that meets the goal and respects the principles explained above.

Different methods can be devised to implement Douglas’ proposals. But the best methods are undoubtedly those that would do it efficiently while making the least amount of changes to existing institutions.

Of course. We need such a service and the banks are very well organized to offer it.

Usually, production undergoes several transformations before finished goods are completed. The first producer involved in the process may need an advance of Credit. When he passes his semi-finished goods on to a second producer he will want to be paid immediately to cover his costs and to pay back the banker. Neither the first producer nor his banker can wait for the goods to reach their final stage of transformation, which may be several months or even several years. Neither can wait for finished goods to be sold by the dealer and paid for by the consumer before getting their money.

Let us say that three firms are successively involved in the process, firms ‘A’, ‘B’ and ‘C’. Here is how we can conceive the financial operations: ‘A’ needs a loan to mobilize the raw material, to pay the transportation costs, his employees, his utility bills, his power equipment and other overhead charges. He goes to a commercial bank and obtains these Credits.

When ‘A’ sells his semi-finished products to ‘B’, he will include in his price all that he spent including the amount he borrowed, which must be returned to the bank. To this he will add his profit which is his salary. ‘B’ may require a loan to pay all of this to ‘A’ and perhaps to cover his own operating costs: transportation, salaries, overhead charges, etc.

‘B’ will go to the bank and obtain the Credit he needs and will pay ‘A’. With the money obtained from ‘B’, ‘A’ will be able to reimburse the bank.

When ‘B’ passes his semi-finished goods to ‘C’, he will also include all his expenses in the price including his loan from the bank. ‘C’ will also go to the bank to pay what he owes to ‘B’ and to cover his operating costs.

Once paid by ‘C’, producer ‘B’ will settle with his bank.

The same thing will happen when ‘C’ passes his finished goods to the wholesaler. The wholesaler will do what the three producers did which is to obtain a loan from the bank with which to pay ‘C’.

The bank, with its accountants and equipment, is well organized to handle these operations. They can keep track of loans issued and repaid. Douglas’ proposals can be implemented easily using this method of financing whereby loans are granted at the different stages of production while using the present banking system.

No, as explained before, these Credits represent part of the country’s productive capacity which is the result of various activities, natural resources, applied science and the existence of an organized society, etc. These Financial Credits only draw their value from Real Credit which is the country’s productive capacity. The Financial Credit is the numbered expression of Real Credit, of a wealth that is social by nature. At its root, Financial Credit, being a social credit, can only be the property of society.

We can use the existing banking system to place Financial Credit into circulation to mobilize the country’s productive capacity. Later, the Credit will be returned to its source using the same banking system. Banks need not be nationalized to carry out this function.

There is therefore no need for a Central Bank to establish a new network of branches. Neither does the Central Bank need to make its own credit inquiries of borrowers. Similarly, it does not need to involve itself directly with the recalling of Credit after it has been used. All of this can be left to the chartered or commercial banks as they are very competent in this type of work.

But this Financial Credit remains a social instrument and it can only originate in a system devoted solely to the service of the community: a national or provincial Credit Office, or else, in a national Central Bank that would fulfill the function of creating Financial Credit.

They would get it, upon request and without cost, from its very source, the Central Bank. It would be obtained with one obligation only which is to return the same amount to the source after its journey in circulation.

The Central Bank would keep track of what is issued and what is returned. The loans would be debited from the commercial bank’s account and money that is returned would be credited.

There is nothing new in these accounting practices between a Central Bank and the commercial banks. In Canada, each commercial bank already has an account with the Bank of Canada in which debit and credit entries are made every day.

Of course. The banks must be able to meet their expenses, pay their employees’ salaries, cover their overhead charges, and make legitimate profits like any private business.

The banks must also foresee cases where some borrowers will fail to pay back their loans. A borrower’s bankruptcy would not discharge the lending bank of its obligation toward the Central Bank. It would remain responsible to return to its source the Credit it has obtained from society.

Social Credit does not wish for people to be irresponsible, not in the least. Quite the opposite as commercial banks would remain responsible for the Credits they obtained from the Central Bank, and the borrower, whether an individual or a company, would remain responsible to the commercial bank which does the lending. The latter would undoubtedly require guarantees of repayment particularly from new clients or from businesses when a greater risk is involved.

The fees that the banks charge for their loans could still be called interest. However the repayment period of the loan should be of lesser importance. Whether the loan stretches over a few months or years, the banker’s financial position is not affected since it is society’s Credit that is in circulation, not his own. At the very most, a longer period would result only in a greater number of bookkeeping entries to the borrower’s account.

Not under a Social Credit financial system that equates purchasing power to prices through the periodic Dividend and the Compensated Discount. Interest charges and all other financial costs are included in prices. They can therefore be recovered through the Means of Payment that will have been placed in the public’s hands.

During the different stages of production the source of financing can be the producer’s personal funds, partly with loans, or even totally with loans, except for the interest costs. This will be determined at the time production is delivered in the form of a finished product. Only then does it become a new production. At the point at which the finished product goes from the wholesaler or last producer to the retailer, an operation will be carried out that fulfills Douglas’ proposal. It is then that new interest free Credits can be issued to cover all the costs necessary for this new production.

Once again, several methods may be used to achieve this. Mr. W. B. Brockie, a New Zealand Social Crediter, suggests that it should be done when the goods are received by the retailer. He would be granted an interest free loan that covers the total cost price of the finished goods. In our view, this method seems to reach a double objective: first, to finance production by new Credit and, secondly, to later allow the Credit to return to its source at the rate goods are consumed.

Production is a continuous flow from raw material to finished product. It becomes finished goods at the point of delivery to the retailer who will undertake its distribution to the consumers.

What is this point or moment of delivery? Delivery occurs at the wholesaler, or at the last producer, if this is where the retailer takes possession of the finished goods.

These finished goods have a price which will be the amount charged to the retailer. This is the cost price of production. However, to obtain the total cost price we must add the distribution costs, that is to say, the retailer’s expenses. And it is this final cost price that must be covered by the issuing of new interest free Credits.

The retailer must therefore add to the wholesaler’s bill his transportation costs, employees’ wages and salaries, the unavoidable losses and his overhead charges. Through experience, he knows the weekly or monthly amounts of these costs. He also knows the average amount of goods he can sell on a weekly or monthly basis. Therefore, he knows the percentage to add to the wholesaler’s bill to get the final cost price of the goods that will be passed on to buyers.

Let us suppose that the retailer knows through experience that the handling and service charges to sell his goods cost on average an amount equal to 10 percent of the price he pays the wholesaler.

Then, let us suppose that this retailer receives a shipment for which he is billed $4,000. He will conclude that he needs $4,400 to cover his total costs: the wholesaler’s price, plus handling costs, but excluding all profits. The $4,400 is the sum of $4,000 + 10 percent of $4,000, i.e. $4,000 + $400 = $4,400.

The final cost price of this new production thus totals $4,400. It is therefore $4,400 of new interest free Credits that are needed to cover the total cost of this new production.

To achieve this, we can use, while improving it, a method of financing used widely among retailers, that is, bank overdrafts. Today, most retailers pay their bills to wholesalers with overdraft cheques. That is to say that, through an agreement between the retailer and his banker, the bank honours these cheques even when the retailer’s account does not have sufficient funds. It is like a loan made on request, in proportion to the retailer’s needs, up to a certain limit which constitutes his “line of credit”. It is very convenient since it allows the wholesaler to be paid immediately so that he may meet his own obligations.

In the bank’s ledger, these overdraft loans are debited against the retailer’s account. As he sells his products, he must return to the bank the fruit of his sales to replenish his account to the banker’s satisfaction. In fact, this is a series of loans and repayments made by mutual agreement. Under the present financial system, the banker charges fees to the retailer for this service. These fees are interest charges calculated on the amount and the duration of the deficits.

Under the proposed system for the financing of new production by new Credits the retailer would pay his bills relative to this production with interest free loans obtained from his bank. This is something which should please retailers.

In the above example, the retailer would get from his bank an interest free loan for $4,400. The chartered bank would draw this amount free of interest from the Central Bank, the source of Credit. Let us remember that we are dealing with a financial system that adapts itself to reality, one that issues credits at the rate goods are produced, and withdraws them at the rate goods are consumed.

| Whereas most economists think in terms of money, Douglas, who was training as an engineer, rather thought in terms of realities: money is the symbol that must reflect realities, and human beings must come before money. |  |

This is so for more than one reason. First, the situation is different. In the producer’s case, the loan is made for a production that does not yet exist, whereas in the retailer’s case, the loan is issued for a production that has already been made. Let us add that the producer did not suffer from having to pay interest, since he included these interest charges in his prices and loans at the subsequent stages of production.

And should the loan to the retailer draw interest, the interest would add to the retail price an element not covered by the loan. Then the new production would no longer be financed entirely by new Credits, as Douglas’ proposal requires for a financial system to reflect reality accurately.

Then again, if interest was charged on the final retail price, this interest would become the property of the commercial bank when the loan was paid back by the retailer. Therefore, part of the Credit would not go back to its source when the goods were consumed, and the system would not reflect reality accurately as Cash Credits, says Douglas, “Shall be cancelled on the purchase of goods for consumption.”

Our retailer therefore gets a $4,400 loan. When he sells his goods, he will return to his bank $4,400 without any additional charges.

When the goods are bought, the money the buyer gives to the retailer stops being Cash Credit and simply becomes Financial Credit. When this Credit is returned to the bank by the retailer it will begin its journey back to its source.

No. For the method proposed here to achieve its goal, the retailer’s profit must not be included in the price paid by the buyer. If his profit was to be included in the retail price, this portion of the retail price would belong to him and would not be returned to the Central Bank to cancel out the Cash Credits. This would cause the same defect we mentioned above.

In the above example, if the retailer was to sell his goods with a 10 percent profit margin, it would raise the retail price to $4,840. This would exceed the new Credit issued to finance this new production by $440. It would distort Douglas’ proposal which requires that all new production be financed by new Credits. Nor would it be suitable to have this profit included in the other costs covered by the amount loaned to the retailer. Increasing this loan to $4,840 and telling the retailer to bring back only $4,400, while keeping the remaining $400 for his profit, would amount to paying the retailer for work not yet performed.

The retailer’s profit must come from a source other than the buyer’s wallet and must come to him only after he has carried out his sale.

Therefore, the retail price will not include the retailer’s profit. This will prevent price increases that are due to the tendency by too many retailers of raising their profit margin when business is good. Under a Social Credit financial system business would always be good since the purely financial problem would be eliminated. To take advantage of this situation by charging exaggerated profits would lead to the inflation of prices whereas the proper flow of production, free of obstacles, should make prices fall.

Not at all. But the retailer’s profit must not depend upon a price increase. His profit would depend rather on the volume of his sales. With a moderate profit margin, determined in advance according to the type of goods for sale, the more items sold the larger his profit. In a non-monopolistic and competitive economy retailers who give customers the best service would generate the most profits, without exceeding the agreed upon profit margin per type of item. Therefore, it is the percentage of profit, not the volume of profit, that must be regulated for each type of business.

Society has the right to demand this of its retailers. Society provides interest free loans to retailers so that they can pay their bills. Also, an equilibrium would thus be maintained at all times between total purchasing power and total price of the goods offered.

Since it is society that provides retailers with the Credit needed to maintain their stock, it is society that is therefore the owner of these goods in a manner of speaking. The retailers are simply the agents in charge of selling them. It is only fair that society should reward the retailers for selling products but without allowing them to exploit buyers.

Therefore, it is society that will provide the retailer’s profit not as a loan that must be paid back but as Cash Credits that will become the retailer’s own property.

The retailer, while remaining the real owner of his private business and managing it freely is at the same time an agent of the community for the distribution of goods. In exactly the same way, the producer keeps his private business but is also an agent of the community to mobilize its Real Credit, that is, the country’s productive capacity. Similarly, the banker remains the owner of his bank but is as well an agent of the community for the circulation, from the Credit Office and back to the Credit Office, of the Financial Credit which is based on the country’s Real Credit.

Social Credit is a firm defender of private property. But every private enterprise also has a social function to fulfill, a function it would automatically fulfill through the simple workings of a Social Credit system faithful to the proposals set forth by Douglas.

Once again, through the chartered bank that will in turn draw this Credit from its social source, the Central Bank or a national Credit Office.

The retailer has two accounts at his bank: his overdraft account, in which the bank keeps a record of the loans made to the retailer and the repayment of these loans and, his personal account, where the retailer can deposit his savings and on which he can issue cheques for his personal affairs, from which he can withdraw cash, etc., like any other individual.

As he sells his goods the retailer returns the money to the bank where it is entered in his commercial account as a repayment of Credit. At the same time the banker enters in the retailer’s personal account the profit to which he is entitled for the sales he made according to the percentage agreed upon for his type of business. For this entry, made in the name of society, the banker issues a cheque drawn upon the national credit, that is to say, on the Central Bank.

For example, if the agreed profit margin is established at 10 percent, with each $100 that the retailer brings as repayment, the banker credits the first account with $100, a Credit which begins its path back to its source. The banker then enters $10 to the credit of the retailer’s personal account.

For all the accounting services performed and not paid by the customers, such as interest free loans, profits to the retailers and periodic Dividends, the banker is reimbursed by the Central Bank according to established practices.

Not at all. Many sentences are needed to explain it but it would soon work in a routine manner as efficiently as banking operations do today in all local banks.

It is infinitely less complicated than the accounting used by consumer co-operatives, where the accountant must keep track of each of the member’s purchases, to distribute to each one a rebate in direct proportion to purchases.

Furthermore, this system would be sound and would reflect economic facts with precision. It would finance production and consumption efficiently. Economic life would be served to our satisfaction with less bureaucracy, fewer inquiries and fewer financial operations than is required today, when government institutions try to settle the deficiencies in purchasing power from which the whole economy suffers. The system would do away with the heavy tax burden now needed to put bread on the table of the less fortunate. It would also end the poor being subjected to lengthy and humiliating questions.

Different by its results, yes, but in all points similar to the present system.

The same banking establishments, bankers, debit and credit entries in bank accounts, payment system by cheques, formalities for loans to producers, responsibilities on the part of lenders and borrowers and overdraft payment options for retailers but without interest fees reflect the similarities to the present system.

Add to this that total purchasing power would be maintained at the same level as total production with a correct share guaranteed to each one. This would result in a better distribution, in the sharing of the fruits of production, in the protection against unjustified price increases and in the abolition of the money dictatorship.

Then, consider the final situation in relation to the $4,400 worth of production as an example.

It was possible to carry out that production without any financial limitations. Credit came according to the needs from one stage of the production process to the next. All participants were duly paid including the bankers who received interest on loans for their services. The complete final payment, which covered financial costs and production costs, could be made as soon as the goods were finished by the interest free loan to the retailer who took possession of this production. The production could then be sold without adding any charges to the cost price.

The financial machinery uses the same mechanisms, but under a Social Credit system, it is properly lubricated instead of sand being allowed into its gearbox, making a world of difference in its operations.

Follow the Credit’s trajectory outlined in these pages. Credit does not pile up. It follows the movement of wealth. It comes into circulation at the rate goods are produced and takes the return route to its source at the rate goods are consumed.

These Credits make up what could be called an operating capital which belongs to society and is placed at the service of the economy so that it can meet the needs of the population in accordance with the physical means that now exist. This working capital can be increased as needs increase and are limited only by reaching full productive capacity.

With its periodic Dividend to all, Social Credit guarantees our sharing in the fruits of production. This topic will be addressed further.

Previous chapter - Douglas's Three Proposals |

Next chapter - Financing Public Works |

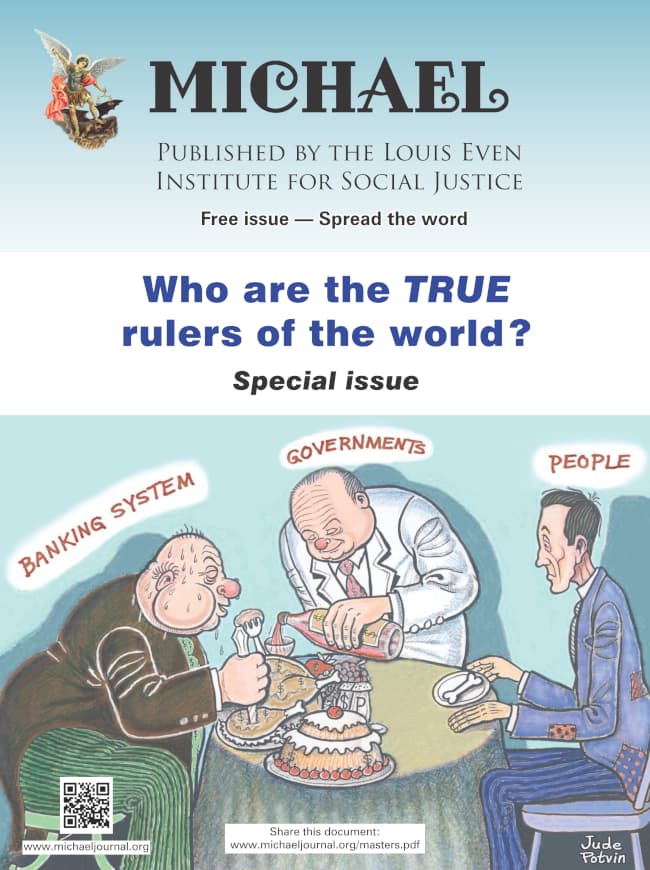

In this special issue of the journal, MICHAEL, the reader will discover who are the true rulers of the world. We discuss that the current monetary system is a mechanism to control populations. The reader will come to understand that "crises" are created and that when governments attempt to get out of the grip of financial tyranny wars are waged.

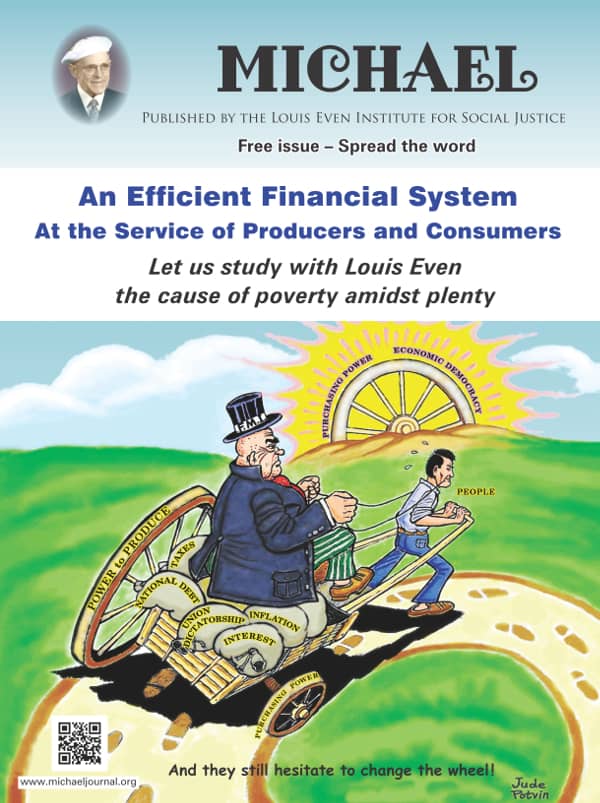

In this special issue of the journal, MICHAEL, the reader will discover who are the true rulers of the world. We discuss that the current monetary system is a mechanism to control populations. The reader will come to understand that "crises" are created and that when governments attempt to get out of the grip of financial tyranny wars are waged. An Efficient Financial System, written by Louis Even, is for the reader who has some understanding of the Douglas Social Credit monetary reform principles. Technical aspects and applications are discussed in short chapters dedicated to the three propositions, how equilibrium between prices and purchasing power can be achieved, the financing of private and public production, how a Social Dividend would be financed, and, finally, what would become of taxes under a Douglas Social Credit economy. Study this publication to better grasp the practical application of Douglas' work.

An Efficient Financial System, written by Louis Even, is for the reader who has some understanding of the Douglas Social Credit monetary reform principles. Technical aspects and applications are discussed in short chapters dedicated to the three propositions, how equilibrium between prices and purchasing power can be achieved, the financing of private and public production, how a Social Dividend would be financed, and, finally, what would become of taxes under a Douglas Social Credit economy. Study this publication to better grasp the practical application of Douglas' work.  Reflections of African bishops and priests after our weeks of study in Rougemont, Canada, on Economic Democracy, 2008-2018

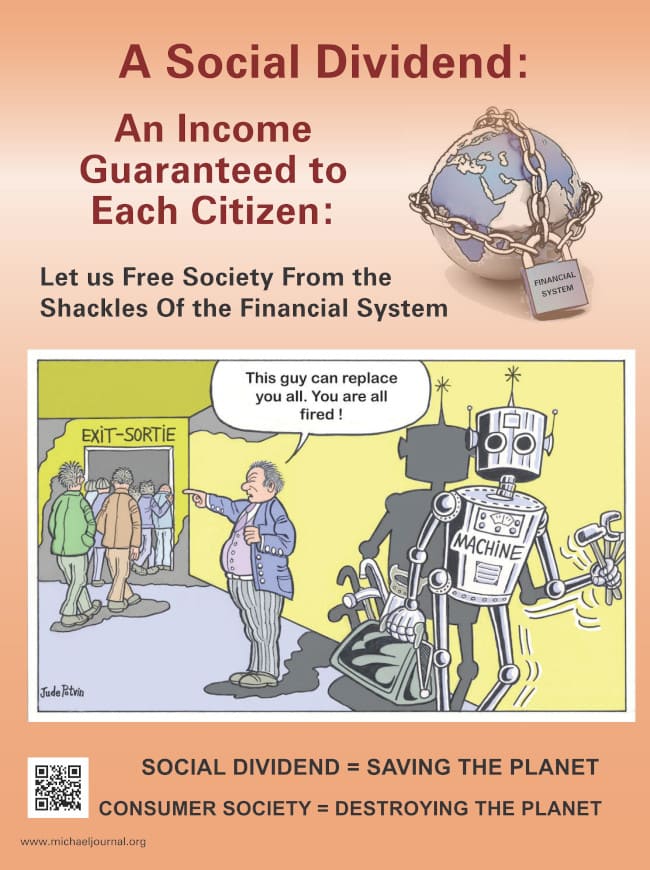

Reflections of African bishops and priests after our weeks of study in Rougemont, Canada, on Economic Democracy, 2008-2018 The Social Dividend is one of three principles that comprise the Social Credit monetary reform which is the topic of this booklet. The Social Dividend is an income granted to each citizen from cradle to grave, with- out condition, regardless of employment status.

The Social Dividend is one of three principles that comprise the Social Credit monetary reform which is the topic of this booklet. The Social Dividend is an income granted to each citizen from cradle to grave, with- out condition, regardless of employment status.Rougemont Quebec Monthly Meetings

Every 4th Sunday of every month, a monthly meeting is held in Rougemont.

Comments (1)

Pedro

Unfortunately, I couldn't understand the trajectory of profit and interest received by the producer and the bank at the beginning of the production process. You say about why the bank cannot charge the retailer interest:

"if interest was charged on the final retail price, this interest would become the property of the commercial bank when the loan was paid back by the retailer. Therefore, part of the Credit would not go back to its source when the goods were consumed"

However, I don't understand how the interest the bank charged the producer could go back to its origins. I make the same question regarding the profit charged by the producer.

I will be very grateful if you can answer my question. Hugs.

reply