The chronic shortage of puchasing power - The social dividend to every citizen

Economic Democracy - Lesson 5

Financing production is not enough. Goods and services must also reach those who need them. In fact, the only reason for the existence of production is to meet needs and wants. Production must be distributed. How is it distributed today, and how would it be distributed under a Social Credit system?

Financing production is not enough. Goods and services must also reach those who need them. In fact, the only reason for the existence of production is to meet needs and wants. Production must be distributed. How is it distributed today, and how would it be distributed under a Social Credit system?

Today, goods are put up for sale at certain prices. People who have money buy these goods by passing over the counter the required sum. This method allows those who have money to buy the goods that they want and need.

Now, Social Credit would in no way change this method of distributing goods. The method is flexible and good — provided, of course, that individuals who have needs also have the purchasing power to choose and buy the goods which would fill these needs.

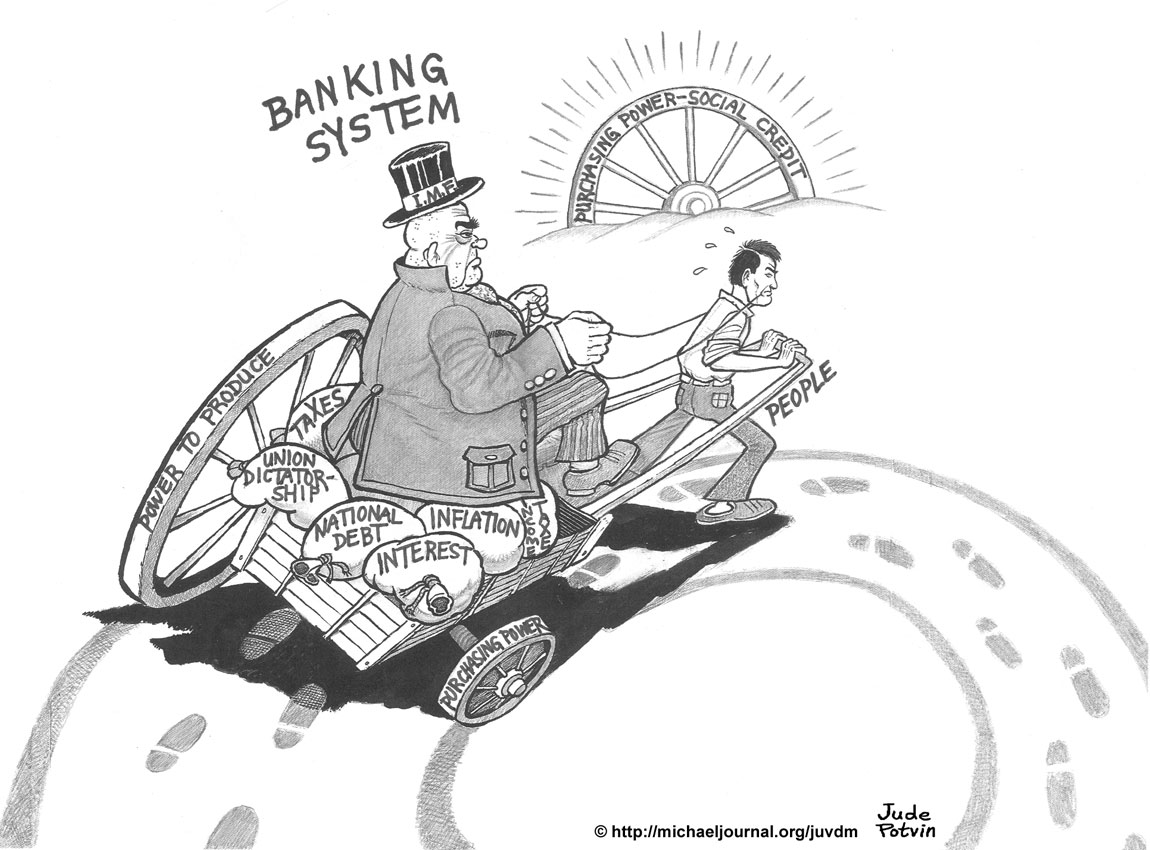

Purchasing power in the hands of those who have needs and wants: it is precisely here that the present system is defective, and it is this defect that Social Credit would correct.

The money distributed in the form of wages, profits, and industrial dividends constitutes purchasing power for those who receive these various allotments. But there are a few flaws in the present system:

- Industry never distributes purchasing power at the same rate that it generates prices.

- The production system does not distribute purchasing power to everyone. It distributes it only to those who are employed in production.

And they still hesitate to change the wheel!

Even if the banks charged no interest, at any given moment, the amount of money available to the community as purchasing power is never sufficient to buy back the total production made by industry.

The economists maintain that production automatically finances consumption; that is to say, that the wages and salaries distributed to the consumers are sufficient to buy all the available goods and services. But facts prove just the opposite. Scottish engineer Clifford Hugh Douglas was the first to demonstrate this chronic shortage of purchasing power. He explained it this way:

A cannot buy A+B

The producer must include all his production costs in the price of his product. The wages distributed to the employees (which for convenience’s sake can be labeled "A" payments) are only one part of the cost price of the product. The producer has other costs besides wage costs (which are labeled "B" payments), that are not distributed in wages and salaries, such as the payments for raw materials, taxes, banking charges, depreciation charges (to replace machinery), etc.

The retail price of the product must include all the costs: wages (A) and other payments (B). So the retail price of the product must be at least A + B. Then, it is obvious that the wages (A) cannot buy the sum of all the costs (A + B). So there is a chronic shortage of purchasing power in the present system.

There are more reasons for this gap between prices and purchasing power: When a finished good is put on the market, it comes with a price attached to it. But part of the money included in this price was distributed perhaps six months or a year ago, or even more. Another part will be distributed only once the good is sold, and the merchant takes out his profit. Another part will perhaps be distributed in ten years, when worn machinery — of which wear is included as an expense in the price — is replaced by new machinery, etc.

Then there are those individuals who receive money, and who do not spend it. This money is included in the prices, but it is not in the purchasing power of those who need goods.

The repayment of short-term bank loans, and the present fiscal system, increase the gap between the prices and the purchasing power. Hence the accumulation of goods, unemployment, and all that ensues.

Some people might say that the businesses paid with "B" payments (those that supplied the raw material, machinery, etc.) then paid wages to their own employees, and part of these "B" payments therefore become "A" payments. This changes nothing of what has been said before: this is simply a wage distributed in another step of production, and this "A" wage cannot be distributed without being included into a price, which cannot be less than A + B; the gap is still there.

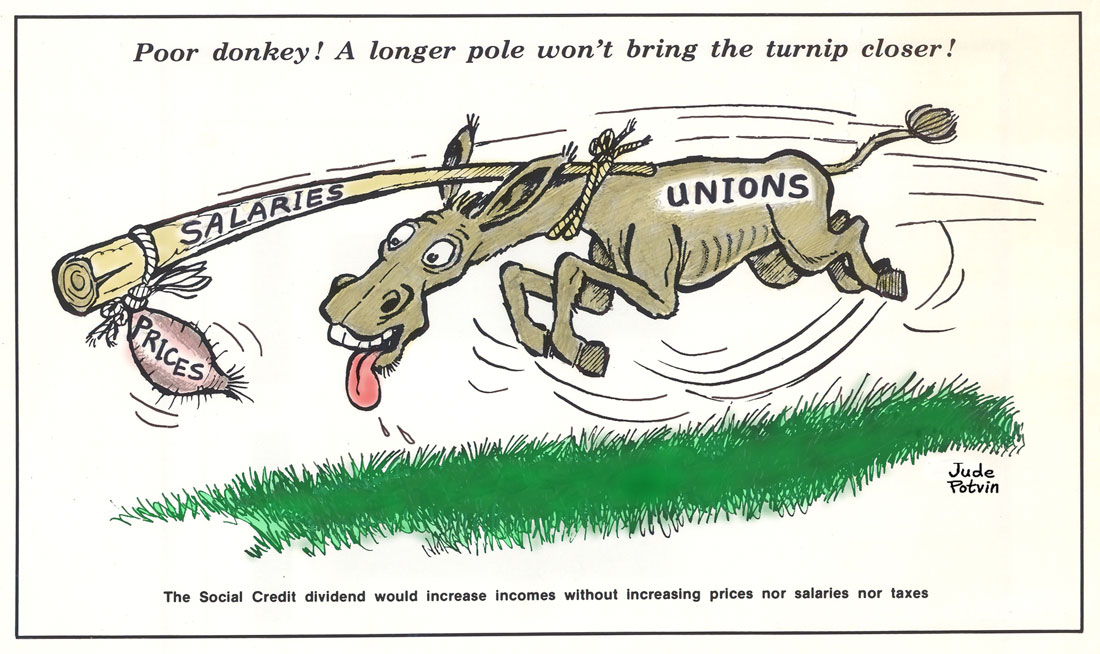

If you try to increase wages and salaries, the wage increases will automatically be included in the prices, and it will accomplish nothing. (Like the donkey on the cartoon running after the turnip.) To be able to buy all of the production, an additional income is needed coming from a source other than wages and salaries, an income at least equivalent to B. This is what the Social Credit dividend would do, being given every month to every citizen in the country. (This dividend would be financed with new money created by the nation, and not by the taxpayers’ money.)

What has kept the system going

Without this other source of income (the dividend), there should be, theoretically, a growing mountain of unsold goods. But if goods are sold all the same, it is because, instead, we have a growing mountain of debt! Since people do not have enough money, retailers must encourage credit buying in order to sell their goods: buy now, pay later (or should we say more precisely, pay forever...) But this is not sufficient to fill the gap in the purchasing power.

Without this other source of income (the dividend), there should be, theoretically, a growing mountain of unsold goods. But if goods are sold all the same, it is because, instead, we have a growing mountain of debt! Since people do not have enough money, retailers must encourage credit buying in order to sell their goods: buy now, pay later (or should we say more precisely, pay forever...) But this is not sufficient to fill the gap in the purchasing power.

So there is also a growing stress upon the necessity for work that distributes wages without increasing the quantity of consumer goods for sale, such as public works (building bridges or roads), war industries (building submarines, airplanes, etc.). But this is not sufficient either.

So each country will strive to achieve a "favourable balance of trade", that is to say, to export, to sell to other countries more goods than it receives, in order to obtain from these foreign countries, the money that the population is lacking at home to buy their own products. However, it is impossible for all nations to have a "favourable balance of trade": if some countries manage to export more goods than they import, there must also necessarily be countries that receive more goods than they export. But no country wishes to be in that position, so it causes trade conflicts between nations that can degenerate into armed conflicts.

Then as a last resort, economists have discovered a new export market, a place where we can send our goods without anyone trying to send anything back, a place where there are no inhabitants: the moon, outer space. Some countries will spend billions of dollars building rockets to go to the moon or other planets; this huge waste of resources is just to generate wages that will be used to buy the production left in our countries. Our economists are really in the clouds!

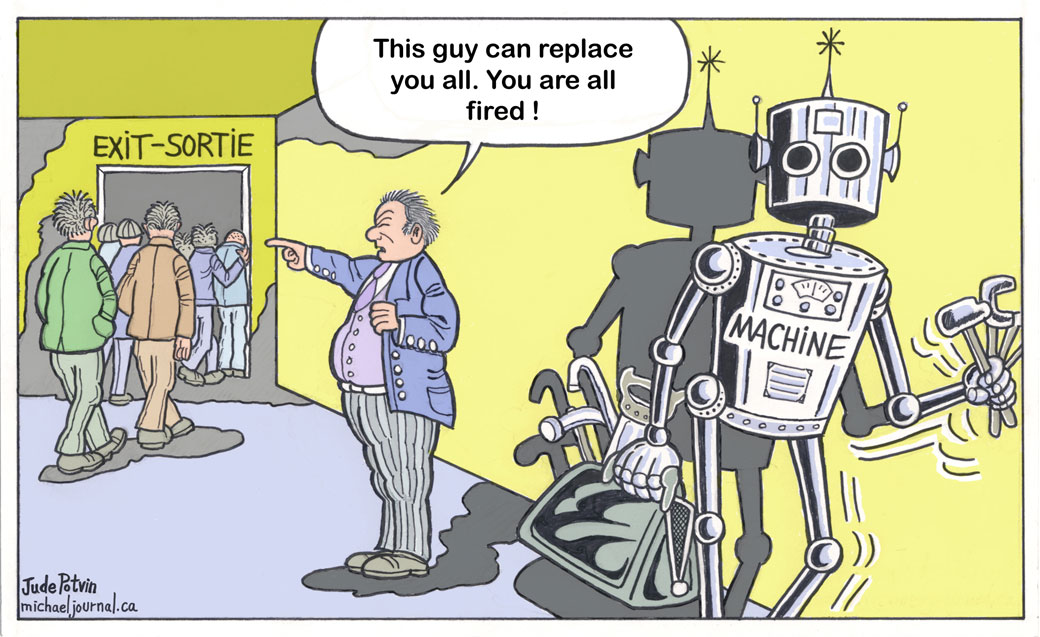

Progress replaces the need for human labour

The second flaw in the present system is that the production system does not distribute purchasing power to everyone. It distributes it only to those who are employed in production. And the more the production comes from the machine, the less it comes from human labour. Production even increases, whereas required employment decreases. So there is a conflict between progress, which eliminates the need for human labour, and the system, which distributes purchasing power only to the employed.

Yet, everybody has the right to live. And everybody is entitled to the basic necessities of life. Earthly goods were created by God for all men, and not only for those who are employed, or employable.

That is why Social Credit would do what the present system is not doing. Without in any way disturbing the system of reward for work, it would distribute to every individual a periodical income, called a "social dividend" — an income tied to the individual as such, and not to employment.

Earthly goods created for all

This is the most direct and concrete means to guarantee to every human being the exercise of his fundamental right to a share in the goods of the earth. Every person possesses this right — not as an employee in production, but simply as a human being.

Pope Pius XII said in his Pentecost radio-address of June 1, 1941:

Pope Pius XII said in his Pentecost radio-address of June 1, 1941:

"Material goods have been created by God to meet the needs of all men, and must be at the disposal of all of them, as justice and charity require.

"Every man indeed, as a reason-gifted being, has, from nature, the fundamental right to make use of the material goods of the earth, though it is reserved to human will and the juridical forms of the peoples to regulate, with more detail, the practical realization of that right.

"Such an individual right cannot, by any means, be suppressed, even by the exercise of other unquestionable and recognized rights over natural goods.

"The economic wealth of a nation does not properly consist in the abundance of goods judged by a sheer material computation of their worth, but it consists in what such an abundance does really and effectively mean and provide as a sufficient material basis for a fair personal development of its members.

"If such a just distribution of goods were not to be effected or just imperfectly ensured, the true end of the national economy would not be achieved, opulent though the abundance of available goods might be, since the people would not be rich, but poor, as it would not be invited to share in that abundance.

"Obtain, on the contrary, that this just distribution be efficiently realized on a durable basis, and you will see a people, though with less considerable goods at its disposal, become economically sound. "

The Pope said that it is up to the peoples themselves, through their laws and regulations, to choose the methods capable of allowing each man to exercise his right to a share in the earthly goods. The Social Credit dividend to all would achieve this. No other proposed system has been, by far, so effective, not even our present social security laws.

Why a dividend to all

— A social dividend to all? But a dividend presupposes a productive-invested capital!

Precisely! It is because all members of society are co-capitalists of a real and immensely productive capital.

We said above, and we could never repeat it enough, that financial credit is, at birth, the property of all of society. It is so because it is based on real credit, on the country’s production capacity. This production capacity is made up partially of work, and the competence of those who also take part in production. But it is mainly made up of other elements which are the property of all.

There are, first of all, natural resources, which are not the production of any man; they are a gift from God, a free gift that must be at the service of all. There are also all the inventions made, developed, and transmitted from one generation to the next. It is the biggest production factor today. No man can claim to be the only owner of progress, which is the fruit of many generations.

No doubt that one needs men of our present times to make use of this progress — and they are entitled to a reward: they get it in remuneration: wages, salaries, etc. But a capitalist who does not personally take part in the industry where he invested his capital is entitled to a share of the result just the same, because of his capital.

The largest real capital of modern production is, in fact, the sum total of the progressive inventions, i.e. discoveries, which today give us more goods with less work. And since all human beings are, on an equal basis, coheirs of this immense capital that is always increasing, all are entitled to a share in the fruits of production.

The employee is entitled to this dividend and to his wage or salary. The unemployed person has no wage or salary, but is entitled to this dividend, which we call social, because it is the income from a social capital.

We have just shown that the Social Credit dividend is based on two things: the inheritance of natural resources, and the inventions from past generations. This is exactly what Pope John Paul II wrote in 1981 in his Encyclical letter Laborem Exercens on human work (n. 13):

"Through his work man enters into two inheritances: the inheritance of what is given to the whole of humanity in the resources of nature, and the inheritance of what others have already developed on the basis of those resources, primarily by developing technology, that is to say, by producing a whole collection of increasingly perfect instruments for work. In working, man also "enters into the labor of others."

The folly of full employment

To speak of full employment, that is of universal employment, is to make a contradiction with the pursuit of progress in the techniques and processes of production. New and more perfect machines are not introduced to tie man to employment, nor are new sources of energy tapped for this end, but rather they are brought into production for the purpose of liberating man from work.

But, alas, we seem to have lost sight of ends. We are confusing means and ends, we mistake the former for the latter. This is a perversion, which infects our whole economic life and which makes it impossible for men to enjoy the logical rewards of progress to the full.

Industry does not exist to give employment, but to furnish products, goods. If it succeeds in furnishing such goods, then it has accomplished its purpose, met its end. And the more completely it meets this end with the minimum of time and the minimum employment of human hands, the more perfect it is.

Mr. Jones, for example, buys his wife an automatic washing machine. Now the weekly wash will take only a quarter of the day instead of a full day. When Mrs. Jones puts the clothing in the washing machine along with the soap, when she turns on the taps bringing in the proper mixture of hot and cold water, she has nothing more to do except to turn on the machine. The machine washes the clothes, rinses them, and then stops automatically when the clothes are ready to come out.

Is Mrs. Jones going to bemoan the fact that she now has more time to do what she pleases? Or is Mr. Jones going to search for another type of work to replace that from which his wife has been freed? Certainly not. Neither one is that stupid.

But we do find such stupidity running rampant in our social and economic life, for the system makes progress penalize the individual, instead of bringing him relief, in that it persists in tying purchasing power, the distribution of money, to employment and employment alone — employment in production. Money comes only as a recompense for effort and labour in production.

It is true that production distributes money to those who are employed in the work of producing. But this is as a means, and not as an end. The purpose of production is not to supply money, but to furnish goods and services. And if production is able to replace twenty salaried individuals by the introduction of one machine, it has not in any way thwarted its true purpose. And if it could furnish all the production necessary for humans, and not distribute one cent of money, it would still be meeting the end for which it exists: to furnish goods and services.

When purchasing power disappears

In freeing men from labour, industry should certainly receive the same gratitude which Mr. Jones received from his wife when he liberated her from hours of work by purchasing an automatic washing machine for her.

But how can a man say "thank you" when he has been liberated from work by a machine, when he finds to his consternation that he has no money? This is precisely where our economic system has become defective, in that it has not adapted its financial mechanism to its productive mechanism.

In the measure that industry or production passes out of human hands, so too should purchasing power, in the form of money, be channeled to consumers through some other means than just recompense for employment. In other words, the financial system should harmonize with production, not only with respect to volume, but also with respect to the manner in which it is distributed. If production is abundant, then money should be abundant. If production is liberated from human labour, then money should be liberated and separated from employment.

Money is an integral part of the financial system, and not a part of the production system, strictly speaking. When the production system finally reaches a point where it can distribute goods without the aid of salaried individuals, then too the financial system should reach the point where purchasing power can be distributed by some other means than salaries.

If such is not the case, it is because, unlike the production system, the financial system has not adapted itself to progress. And it is precisely this difference which has given rise to grave problems, when in fact progress should make all problems of such a nature disappear.

Replacing men by machines in production should lead to the enrichment of men, to their deliverance from purely material worries and cares, permitting them to give themselves over to human pursuits other than those which are related solely to the economic function. If, on the contrary, such a substitution leads to privation, it is because we have refused to adapt the financial system to this progress.

Technology should serve every man

Is technology an evil? Should we rise up and destroy the machines because they take our jobs? No, if the work can be done by the machine, that is just great; it will allow man to give his free time over to other activities, free activities, activities of his own choosing. But this providing he is given an income to replace the salary he lost with the installation of the machine, of the robot; otherwise, the machine, which should be the ally of man, will become his enemy, since it deprives him of his income, and prevents him from living:

"Technology has contributed so much to the well-being of humanity; it has done so much to uplift the human condition, to serve humanity, and to facilitate and perfect its work. And yet at times technology cannot decide the full measure of its own allegiance: whether it is for humanity or against it... For this reason my appeal goes to all concerned... to everyone who can make a contribution toward ensuring that the technology which has done so much to build Toronto and all Canada will truly serve every man, woman and child throughout this land and the whole world." (John Paul II, homily in Toronto, Canada, September 15, 1984.)

In 1850, manufacturing as we know it today was barely started, with man doing 20% of the work, animals 50%, and machines accounting for only 30%. By 1900, man was doing only 15%, animals 30%, and machines 55%. By 1950, man was doing only 6%, and machines the rest — 94%. (The animals have been freed!)

And we have seen nothing yet, since we are only entering the computer age, which allows places like the Nissan Zama plant in Japan to produce 1,300 cars a day with the help of only 67 humans — that is more than 13 cars a day per man. There are even some factories that are entirely automated, without any human employee, like the Fiat motor factory in Italy, which is under the control of some twenty robots who do all the work.

In 1964, a report was presented to the President of the United States, signed by 32 signatories, including Mr. Gunnar Myrdal, Swedish-born economist, and Dr. Linus Pauling, winner of the Nobel Prize, entitled "Social Chaos in Automation". This report said in brief that "the U.S., and eventually the rest of the world, would soon be involved in a ‘revolution’ which promised unlimited output… by systems of machines which will require little co-operation from human beings. Consequently, action must be taken to ensure incomes for all men, whether or not they engage in what is commonly reckoned as work."

In his book The End of Work, U.S. author Jeremy Rifkin quotes a recent Swiss study which said that "in thirty years from now, less than 2% of the present workforce will be enough to produce the totality of the goods that people need." Three out of every four workers — from retail clerks to surgeons — will eventually be replaced by computer-guided machines.

If the rule that limits the distribution of income to those who are employed is not changed, society is heading for chaos. It would be plain ludicrous to tax 2% of workers to support 98% of unemployed people. We definitely need a source of income that is not tied to employment. The case is clearly made for the Social Credit dividend.

Full employment is materialistic

If we must blindly persist in keeping everyone, men and women alike, employed in production, even though the production to meet basic needs is made with less and less human labour already, then new jobs, which are completely useless, must be created. And in order to justify these useless jobs, new artificial needs must be created, through an avalanche of advertisements, so that people will buy products they do not really need. This is what is called "consumerism".

Likewise, products will be manufactured to last as short a time as possible, with the intent of selling more of them and making more money, which brings about an unnecessary waste of natural resources, and also the destruction of the environment. Also, we persist in maintaining jobs that require no creative efforts whatever, jobs that require only mechanical efforts, jobs that could well be done by machines, jobs where the employee has no chance of developing his personality. But, however mind-destroying this job is, it is the condition for the worker to obtain money, the licence to live.

Thus, for all wage-earners, the meaning of their jobs comes down to this: they go to work to get the cash to buy the food to get the strength to go to work to get the cash to buy the food to get the strength to go to work... and so on, until retiring age, if they do not die before. Here is a meaningless life, where nothing differentiates man from an animal.

Free activities

In his 1936 movie Modern Times, Charlie Chaplin gives an example of dehumanizing work, by playing a machine worker who suffers temporary derangement, as he tightens the bolts on a factory treadmill at a frantic pace.

In his 1936 movie Modern Times, Charlie Chaplin gives an example of dehumanizing work, by playing a machine worker who suffers temporary derangement, as he tightens the bolts on a factory treadmill at a frantic pace.What differentiates man from an animal is precisely that man has not only material needs, but also cultural and spiritual needs. As Jesus said in the Gospel: "Not on bread alone does man live, but in every word that proceeds from the mouth of God" (Deuteronomy 8:3.). So to force man to spend all his time in providing for his material needs is a materialistic philosophy, since it denies that man has also a spiritual dimension and spiritual needs.

But, then, if man is not employed in a paid job, what will he do with his spare time? He will spend it on free activities, activities of his own choosing. It is precisely in his leisure time that man can really develop his personality, develop the talents that God gave him, and use them wisely.

Moreover, it is during their leisure time that a man and a woman can take care of their religious, social, and family duties: raising their family, practising their Faith (to know, love, and serve God), and help their brothers and sisters in Christ. Raising children is the most important job in the world. Yet because the mother, who stays at home to raise her children, receives no salary, many will say that she does nothing, that she does not work! (Ask any stay-at-home mother if she does not work!)

To be freed from the necessity of working to produce the necessities of life does not presume growing idleness. It simply means that the individual would be placed in the position where he could participate in the type of activity which appeals to him. Under a Social Credit system, there would be an outburst of creative activity. For example, the greatest inventions, and the best works of art, have been made during leisure time. As C. H. Douglas said:

"Most people prefer to be employed, but on things they like rather than on the things they don’t like to be employed upon. The proposals of Social Credit are in no sense intended to produce a nation of idlers... Social Credit would allow people to allocate themselves to those jobs to which they are suited. A job you do well is a job you like, and a job you like is a job you do well."

Full employment is outmoded

This exactly what Pope John Paul II said on November 18, 1983, when he received in audience the participants in a national conference sponsored by the Italian Episcopal Conference’s Commission for Social Problems and Work. Here are excerpts from the Pope’s address:

This exactly what Pope John Paul II said on November 18, 1983, when he received in audience the participants in a national conference sponsored by the Italian Episcopal Conference’s Commission for Social Problems and Work. Here are excerpts from the Pope’s address:

"The primary foundation of work is in fact man himself... Work is for man and not man for work... Furthermore, we cannot fail to be concerned about the opinions of those who today hold that discussion of a more intense participation is now outmoded and useless, and demand that human subjectivity be realized in so-called free time. It does not seem just, in fact, to oppose the time dedicated to work to the time that is free of work, in so far as all man’s time must be viewed as a marvellous gift of God for overall and integral humanization. I am nevertheless convinced that free time deserves special attention because it is the time when people can and must fulfil their family, religious, and social obligations. Rather, this time, in order to be liberating and useful socially, is spent with mature ethical awareness in a perspective of solidarity, which is also expressed in forms of generous volunteer services." (Taken from L’Osservatore Romano, weekly edition in English, January 9, 1984, p. 18.)

| Previous chapter - The solution: debt-free money issued by society | Next chapter - Money and prices – The compensated discount |