Financing Public Works

What was just explained shows how Douglas’ financial proposals could be applied to the production and distribution of consumer goods. Could this method be applied also to the production and payment of public works?

Definitely! In this case, consumption is the gradual “wear and tear” that accompanies the aging of public works.

Public works such as schools, waterworks, municipal buildings, roads, sidewalks and sewer systems are consumed by everyone. Once built these public works are a new production which must be financed by new Credits.

In the case of consumer goods, producers use the existing financial system including bank loans that charge interest fees. These costs are covered by interest-free social credits when the finished goods go from the wholesaler to the retailer who serves consumers. Would this be the same for public works? When would the financial costs of this new production be covered by interestfree Credits?

Usually, governments and other public administrations entrust contractors with the execution of these projects. Most often, the lowest bidder is chosen after his competency and liability are assessed.

The contractor would finance himself in the same manner as do the producers of consumer goods.

As for the new Credits to finance these public works, the public administration that initiated the project would secure interest-free Credits to pay the contractor when the project was completed.

After a public work is delivered the population, which is the consumer in this case, would begin to pay for its consumption, i.e its wear and tear.

Would you explain this by an example?

We have seen at the beginning of this study that a country’s Real Credit resides in that country’s productive capacity.

Therefore, all new Financial Credit must come from a Monetary Office, which can be a Central Bank, operating on behalf of society. But this Credit can be directed toward production by the system of banks that now exist and be returned to its source using the same banks.

We have also said that the Monetary Office could be the Bank of Canada on a national level, or a provincial Credit Office on a provincial level. For this example, let us suppose that Social Credit is established in all of Canada.

Government representatives at the federal, provincial, or municipal levels need not wonder whether these projects are financially possible, but only whether they answer real needs and whether they are physically feasible. By physically feasible, we are asking if the country’s productive capacity is capable of carrying out these public works while continuing to supply the goods required to answer private needs. Or will this new public project prevent a more urgent production from being made?

The decision to proceed or to postpone work on the submitted projects will be made accordingly, setting aside financial considerations. Finance will carry out its role which is to serve. Balanced budgets would no longer be a consideration. Our only priority would be to determine the order in which feasible works are begun.

The decision to proceed or to postpone the projects that were submitted will be taken accordingly, with financial considerations set aside. Finance will carry out its role: to serve without deciding. Balanced budgets would no longer be a consideration; our only priority would be to determine in what order we want works to be carried out, works that are wanted and feasible.

For instance, let us consider the building of a bridge. The decision to build was made because it answers a real need and because there is no reason to fear that activities directed toward this construction would prevent stores from being supplied with consumer goods.

In a Social Credit system the financing of the bridge is not a concern. The government will nevertheless ask that tenders be submitted. Selection of the lowest bid would mean that fewer materials and less energy and time would be used and ensure a smaller portion of the country’s real wealth would be dedicated to the project.

Let us say that John Smith is awarded the contract after a bid of $5,000,000. This bid reflects all his expenses and a legitimate profit. He has already calculated how much he needs to borrow to pay for the materials, his employees’ wages and for interest. He owns the construction company, the government doesn’t. His only guarantee is that once the bridge is completed, he will receive $5,000,000 from the government if its inspection shows that the bridge was built according to agreed upon standards.

Whether Mr. Smith is compelled to borrow $2,000,000, or $3,000,000, or even the total amount of $5,000,000 is his own concern. If he deals with a bank they will settle the matter between themselves. The government has no part in this.

As was the case with private production if Smith borrows the money from the bank, it is justified in requiring that he pay interest to cover its own operating costs. Once completed the bridge is John Smith’s property but it is of no particular use to him and he will want to deliver it to the government. After a successful inspection the government will pay him the agreed upon price.

This price includes all material and labour costs, anticipated financial costs and the profit John Smith included in his bid.

If financial costs include interest charged on his loan does this mean that this new production will not be paid with new interest-free money?

Yes, it will be paid with new interest-free money just as was the retailer when dealing with consumer goods. The government will obtain the total amount of new interest-free Credit to pay this newly completed production.

How and where will it get this money?

The Circulation of Financial Credit in a Social Credit System

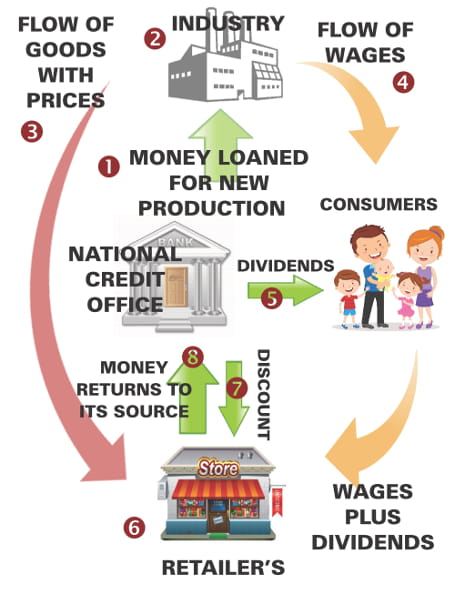

Money is loaned by the National Credit Office (1) to the producers (industry) (2) for the production of new goods. The left arrow shows the flow of goods with their prices attached. (3) The top right arrow depicts earned wages distributed to consumers (who are workers). (4) The horizontal arrow shows the National Credit Office issuing a dividend to each citizen (consumer). (5) Both wages and dividends flow from the consumers to the retailer as sown by the lower right arrow. Both consumers and goods meet at the retailer’s (6) where a final adjustment to prices is made using a compensated discount: (7) Once a product is purchased (consumed), the credits that were created to finance its production and consumption are returned to the National Credit Office. (8) |

It will get it from the source of Financial Credit, that is from the Central Bank, either directly or through a commercial bank.

Is the government now indebted for $5,000,000?

Not at all. There is no getting into debt. The bridge is wealth created by the country’s population. Other workers supplied the things that allowed the bridge to be built such as food and goods of all kinds.

The population must not be put into debt for its own production just as the baker is not required to purchase the bread he has made. If the bridge had been built by Mexico or China, then it would be recorded as a debt owed to Mexico or China. In a sound financial system, in keeping with reality, a public or national debt can only exist if owed to a foreign country.

But in the case of consumer goods the retailer paid back to the bank with no interest, the amount he had obtained to take possession of the finished goods. He was required to return to the bank the Credit obtained as goods were sold.

That is correct! Producers obtain their own loans to produce goods. The retailer obtains a new interest-free loan to pay the producer of the finished goods. The consumer pays for the retail goods.

And in the case of public production, such as the bridge, will the interest-free Credit obtained from the Bank also be returned to its source? And if so, by whom and how?

The same way as with consumer goods. The population does not have to pay for the production of the bridge. Rather the population will pay for its consumption or depreciation. This is in keeping with Douglas’ second proposal: “The credits required to finance production shall be supplied not from savings, but by new credits relating to new production, and shall be recalled only in ratio of general depreciation to general appreciation.”

Let us return to the baker’s bread. The consumer of the bread will pay for its consumption but not for its production. Similarly, the consumer of the bridge will pay for its consumption but not for its production.

How will the population pay for the bridge?

Let us say that the bridge is expected to last for fifty years.

At the end of fifty years, whether the bridge is totally “consumed” or not, payments will no longer be required. Nothing can be consumed twice, nor should it be paid for twice, just as the consumer should not pay the baker twice for his bread.

It is only an absurd and plundering financial system, such as the system we now have, that can make the population pay twice for its waterworks, schools, bridges, roads or even for the wars it has fought and won!

Is it through taxes that the government will withdraw from the public the yearly amounts to be paid for the depreciation of the bridge?

It will withdraw them by means of a levy that can vary, but not necessarily be the present method of taxation, which is cumbersome, expensive, and often unfair.

The wear and tear for a given period would be added to total consumption for that period. As a result the Discount would be slightly lower and would necessarily affect all consumer prices.

And what if by accident or sabotage the bridge should fall down at the end of ten years?

This would raise, at once, by the amount of the value that was lost, the country’s total consumption for the current period and the matter would be settled by the Price Adjustment mechanism.

The outstanding amount would be included in the current period’s consumption. This would be the case since prices, under a Social Credit system, are adjusted by taking cost prices and multiplying them by the ratio of “consumption/production”. In this case, the greater the total consumption relative to total production the smaller would be the Compensated Discount. This is in keeping with the principle that finance must be the exact reflection of reality.

Previous chapter - Financing Production |

Next chapter - Circulation of Money |